Feb 21 2025

Jonathan E. Pekar, Thomas P. Peacock, Louise Moncla, Praneeth Gangavarapu, Divya Venkatesh,

Daniel H. Goldhill, Karthik Gangavarapu, Moritz U. G. Kraemer, Gytis Dudas, Jeffrey B. Joy, Christopher Ruis, Xiang Ji, Meera Chand, Natalie Groves, Oliver G. Pybus, Angela L. Rasmussen, Joel O. Wertheim,

Andrew Rambaut, Philippe Lemey, Michael Worobey

Abstract

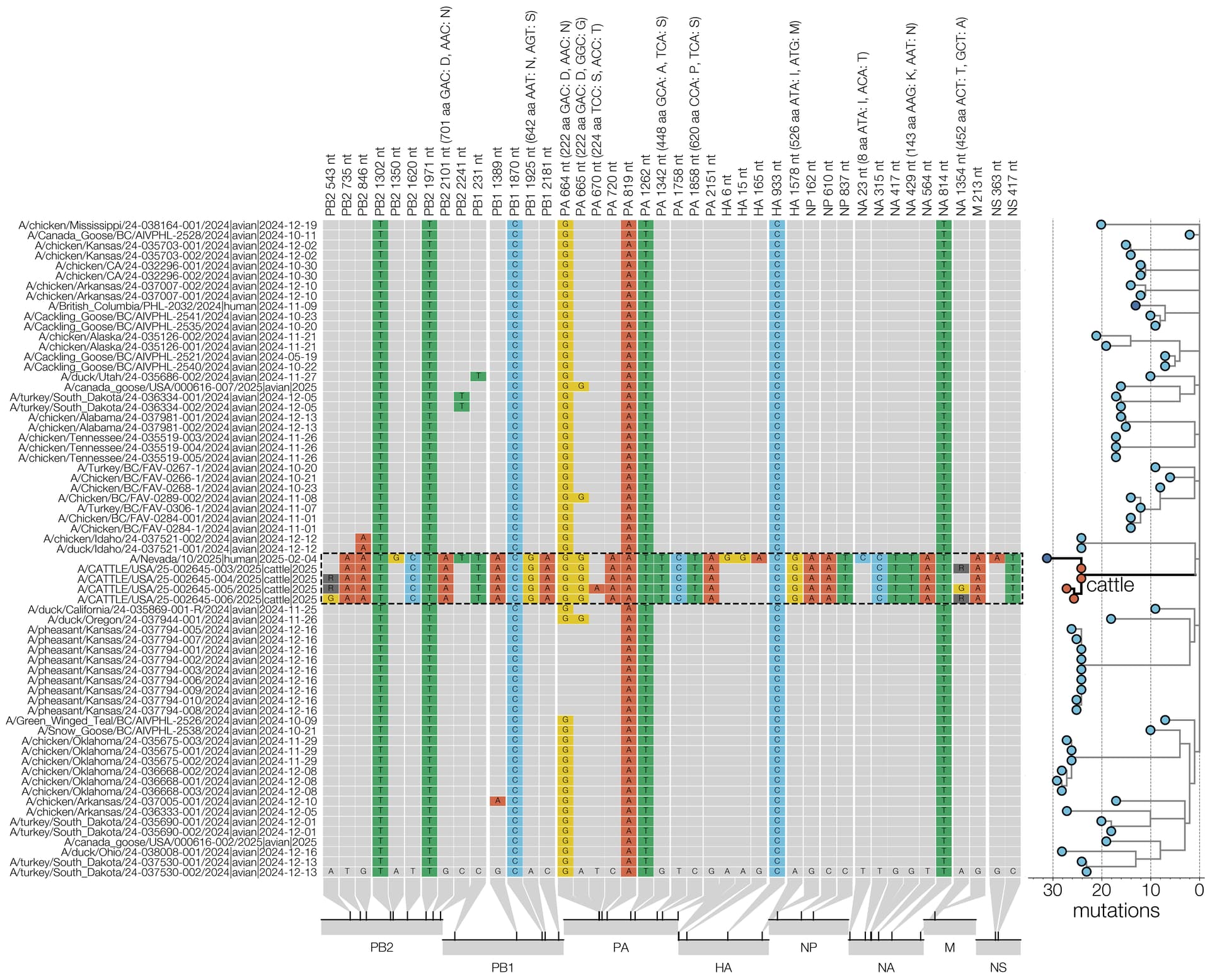

On January 31st, 2025, the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) National Veterinary Services Laboratories identified a new genotype of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus in dairy cattle in Churchill County, Nevada, the second known introduction of clade 2.3.4.4b H5N1 into cattle. Here, we estimate when this virus jumped from the avian reservoir into dairy cattle, using raw sequence reads from four D1.1 bovine H5N1 influenza cases. These data were shared by Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service/USDA on Friday, 7 February 2025. We also characterize mutations in the cattle D1.1 virus sequences and provide a list and brief discussion of mutations that may be of interest or concern. We find that the virus jumped from birds into cattle between late October 2024 and December or early January. Tentative approximations suggest the jump may have happened around the first week of December. This suggests that the origin of this cattle outbreak occurred more than a month before the first quarantines were imposed on two affected farms on January 24th, which had been instituted after the sampling of a local dairy processing plant’s milk silos (January 6th/7th), the testing of these samples (January 10th), and follow-up sample collection (January 17th) and highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) testing (January 24th) at twelve individual farms supplying the silos. Since then, at least four additional infected herds in the area have been identified. Hence, while the discovery of this outbreak illustrates the impressive utility of the National Silo Monitoring Program in detecting outbreaks, our findings suggest that for this program to be most effective in outbreak control, immediate quarantine of all possibly-contributing herds to influenza virus-positive silos might be necessary. Considering the currently widespread nature of H5N1 in the United States, frequent on-site testing, including of individual herds, may be necessary for timely and maximally effective control measures for bovine H5N1 outbreaks.

Jonathan E. Pekar, Thomas P. Peacock, Louise Moncla, Praneeth Gangavarapu, Divya Venkatesh,

Daniel H. Goldhill, Karthik Gangavarapu, Moritz U. G. Kraemer, Gytis Dudas, Jeffrey B. Joy, Christopher Ruis, Xiang Ji, Meera Chand, Natalie Groves, Oliver G. Pybus, Angela L. Rasmussen, Joel O. Wertheim,

Andrew Rambaut, Philippe Lemey, Michael Worobey

Abstract

On January 31st, 2025, the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) National Veterinary Services Laboratories identified a new genotype of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus in dairy cattle in Churchill County, Nevada, the second known introduction of clade 2.3.4.4b H5N1 into cattle. Here, we estimate when this virus jumped from the avian reservoir into dairy cattle, using raw sequence reads from four D1.1 bovine H5N1 influenza cases. These data were shared by Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service/USDA on Friday, 7 February 2025. We also characterize mutations in the cattle D1.1 virus sequences and provide a list and brief discussion of mutations that may be of interest or concern. We find that the virus jumped from birds into cattle between late October 2024 and December or early January. Tentative approximations suggest the jump may have happened around the first week of December. This suggests that the origin of this cattle outbreak occurred more than a month before the first quarantines were imposed on two affected farms on January 24th, which had been instituted after the sampling of a local dairy processing plant’s milk silos (January 6th/7th), the testing of these samples (January 10th), and follow-up sample collection (January 17th) and highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) testing (January 24th) at twelve individual farms supplying the silos. Since then, at least four additional infected herds in the area have been identified. Hence, while the discovery of this outbreak illustrates the impressive utility of the National Silo Monitoring Program in detecting outbreaks, our findings suggest that for this program to be most effective in outbreak control, immediate quarantine of all possibly-contributing herds to influenza virus-positive silos might be necessary. Considering the currently widespread nature of H5N1 in the United States, frequent on-site testing, including of individual herds, may be necessary for timely and maximally effective control measures for bovine H5N1 outbreaks.