PNAS

Microbiota regulates immune defense against respiratory tract influenza A virus infection

Takeshi Ichinohea,b,1,

Iris K. Panga,1,

Yosuke Kumamotoa,

David R. Peaperc,

John H. Hoa,

Thomas S. Murrayc,d, and

Akiko Iwasakia,2

aDepartment of Immunobiology,

dDepartment of Pediatrics, and

cLaboratory Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06520; and

bDepartment of Virology, Faculty of Medicine, Kyushu University, Fukuoka 812-8582, Japan

Edited by Dan R. Littman, New York University Medical Center, New York, NY, and approved February 7, 2011 (received for review December 23, 2010)

Abstract

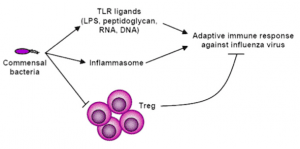

Although commensal bacteria are crucial in maintaining immune homeostasis of the intestine, the role of commensal bacteria in immune responses at other mucosal surfaces remains less clear. Here, we show that commensal microbiota composition critically regulates the generation of virus-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells and antibody responses following respiratory influenza virus infection. By using various antibiotic treatments, we found that neomycin-sensitive bacteria are associated with the induction of productive immune responses in the lung. Local or distal injection of Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands could rescue the immune impairment in the antibiotic-treated mice. Intact microbiota provided signals leading to the expression of mRNA for pro?IL-1β and pro?IL-18 at steady state. Following influenza virus infection, inflammasome activation led to migration of dendritic cells (DCs) from the lung to the draining lymph node and T-cell priming. Our results reveal the importance of commensal microbiota in regulating immunity in the respiratory mucosa through the proper activation of inflammasomes.

Microbiota regulates immune defense against respiratory tract influenza A virus infection

Takeshi Ichinohea,b,1,

Iris K. Panga,1,

Yosuke Kumamotoa,

David R. Peaperc,

John H. Hoa,

Thomas S. Murrayc,d, and

Akiko Iwasakia,2

aDepartment of Immunobiology,

dDepartment of Pediatrics, and

cLaboratory Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06520; and

bDepartment of Virology, Faculty of Medicine, Kyushu University, Fukuoka 812-8582, Japan

Edited by Dan R. Littman, New York University Medical Center, New York, NY, and approved February 7, 2011 (received for review December 23, 2010)

Abstract

Although commensal bacteria are crucial in maintaining immune homeostasis of the intestine, the role of commensal bacteria in immune responses at other mucosal surfaces remains less clear. Here, we show that commensal microbiota composition critically regulates the generation of virus-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells and antibody responses following respiratory influenza virus infection. By using various antibiotic treatments, we found that neomycin-sensitive bacteria are associated with the induction of productive immune responses in the lung. Local or distal injection of Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands could rescue the immune impairment in the antibiotic-treated mice. Intact microbiota provided signals leading to the expression of mRNA for pro?IL-1β and pro?IL-18 at steady state. Following influenza virus infection, inflammasome activation led to migration of dendritic cells (DCs) from the lung to the draining lymph node and T-cell priming. Our results reveal the importance of commensal microbiota in regulating immunity in the respiratory mucosa through the proper activation of inflammasomes.

Comment