January 26, 2021

Lasting immunity found after recovery from COVID-19

At a Glance

- The immune systems of more than 95% of people who recovered from COVID-19 had durable memories of the virus up to eight months after infection.

- The results provide hope that people receiving SARS-CoV-2 vaccines will develop similar lasting immune memories after vaccination.

This long-term immune protection involves several components. Antibodies—proteins that circulate in the blood—recognize foreign substances like viruses and neutralize them. Different types of T cells help recognize and kill pathogens. B cells make new antibodies when the body needs them.

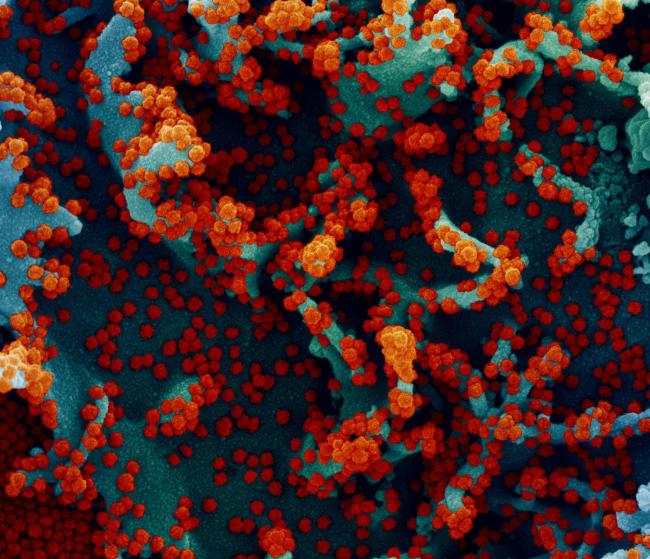

All of these immune-system components have been found in people who recover from SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. But the details of this immune response and how long it lasts after infection have been unclear. Scattered reports of reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 have raised concerns that the immune response to the virus might not be durable.

To better understand immune memory of SARS-CoV-2, researchers led by Drs. Daniela Weiskopf, Alessandro Sette, and Shane Crotty from the La Jolla Institute for Immunology analyzed immune cells and antibodies from almost 200 people who had been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 and recovered.

Time since infection ranged from six days after symptom onset to eight months later. More than 40 participants had been recovered for more than six months before the study began. About 50 people provided blood samples at more than one time after infection.

The research was funded in part by NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and National Cancer Institute (NCI). Results were published on January 6, 2021, in Science.

The researchers found durable immune responses in the majority of people studied. Antibodies against the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, which the virus uses to get inside cells, were found in 98% of participants one month after symptom onset. As seen in previous studies, the number of antibodies ranged widely between individuals. But, promisingly, their levels remained fairly stable over time, declining only modestly at 6 to 8 months after infection.

Virus-specific B cells increased over time. People had more memory B cells six months after symptom onset than at one month afterwards. Although the number of these cells appeared to reach a plateau after a few months, levels didn’t decline over the period studied.

Levels of T cells for the virus also remained high after infection. Six months after symptom onset, 92% of participants had CD4+ T cells that recognized the virus. These cells help coordinate the immune response. About half the participants had CD8+ T cells, which kill cells that are infected by the virus.

As with antibodies, the numbers of different immune cell types varied substantially between individuals. Neither gender nor differences in disease severity could account for this variability. However, 95% of the people had at least 3 out of 5 immune-system components that could recognize SARS-CoV-2 up to 8 months after infection.

“Several months ago, our studies showed that natural infection induced a strong response, and this study now shows that the responses last,” Weiskopf says. “We are hopeful that a similar pattern of responses lasting over time will also emerge for the vaccine-induced responses.”

—by Sharon Reynolds

References: Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Dan JM, Mateus J, Kato Y, Hastie KM, Yu ED, Faliti CE, Grifoni A, Ramirez SI, Haupt S, Frazier A, Nakao C, Rayaprolu V, Rawlings SA, Peters B, Krammer F, Simon V, Saphire EO, Smith DM, Weiskopf D, Sette A, Crotty S. Science. 2021 Jan 6:eabf4063. doi: 10.1126/science.abf4063. Online ahead of print. PMID: 33408181.

Funding: NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and National Cancer Institute (NCI); La Jolla Institute for Immunology; John and Mary Tu Foundation; Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; Mastercard; Wellcome; Emergent Ventures; Collaborative Influenza Vaccine Innovation Centers; JPB Foundation; Cohen Foundation; Open Philanthropy Project.

Earlier research:

June 30, 2020

Potent antibodies found in people recovered from COVID-19

At a Glance

- Although most people who recovered from COVID-19 had low levels of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in their blood, researchers identified potent infection-blocking antibodies.

- Their careful analysis of the antibodies may provide guidance for developing vaccines and antibodies as treatments for COVID-19.

As the global pandemic caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 continues, researchers are working at unprecedented speed to produce new treatments and vaccines. Much work has focused on studying antibodies from the blood of people who have recovered from COVID-19, the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2.

Antibodies are molecules that are produced by the immune system to fight infection. Some research teams are testing whether antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 could be isolated and given as a treatment to others who are infected. Others are studying the structure and function of different antibodies to help guide the development of vaccines.

SARS-CoV-2 particles have proteins called spikes protruding from their surfaces. These spikes latch onto human cells, then undergo a structural change that allows the viral membrane to fuse with the cell membrane. The viral genes then enter the host cell to be copied and produce more viruses.

Several potential vaccines now under development are designed to trigger the human body to produce antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Antibodies that recognize and bind to the spike protein will hopefully block the virus from infecting human cells.

To better understand antibodies against the spike protein that are naturally produced after an infection, a team led by Drs. Davide Robbiani and Michel Nussenzweig at the Rockefeller University studied 149 people who had recovered from COVID-19 and volunteered to donate their blood plasma. The participants had started experiencing symptoms of the virus an average of 39 days before sample collection.

The study was funded in part by NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). Results were published on June 18, 2020, in Nature.

The researchers first isolated antibodies that could bind to the receptor binding domain (RBD), a crucial region on the virus’s spike protein. They then tested whether the antibodies could neutralize SARS-CoV-2—that is, bind to the virus and stop infection.

Most participants had low or very low levels of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Only 1% of the study participants had high levels of antibodies that could neutralize the virus.

To examine the range of antibodies made, the researchers isolated the cells that produce antibodies—memory B cells—from the plasma of six selected participants with very high to moderate levels of neutralizing antibodies. Even in those with modest neutralizing activity in their plasma, the team found potent antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 RBD. Surprisingly, neutralizing antibodies from different people showed remarkable similarity.

Further analysis showed that the neutralizing antibodies fell into three groups, each binding to a different part of the RBD. Together, these insights could help guide the design of vaccines or antibodies as potential treatments for COVID-19.

“We now know what an effective antibody looks like and we have found similar ones in more than one person,” Robbiani says. “This is important information for people who are designing and testing vaccines. If they see their vaccine can elicit these antibodies, they know they are on the right track.”

—by Sharon Reynolds

References: Convergent antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in convalescent individuals. Robbiani DF, Gaebler C, Muecksch F, Lorenzi JCC, Wang Z, Cho A, Agudelo M, Barnes CO, Gazumyan A, Finkin S, Hägglöf T, Oliveira TY, Viant C, Hurley A, Hoffmann HH, Millard KG, Kost RG, Cipolla M, Gordon K, Bianchini F, Chen ST, Ramos V, Patel R, Dizon J, Shimeliovich I, Mendoza P, Hartweger H, Nogueira L, Pack M, Horowitz J, Schmidt F, Weisblum Y, Michailidis E, Ashbrook AW, Waltari E, Pak JE, Huey-Tubman KE, Koranda N, Hoffman PR, West AP Jr, Rice CM, Hatziioannou T, Bjorkman PJ, Bieniasz PD, Caskey M, Nussenzweig MC. Nature. 2020 Jun 18. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2456-9. Online ahead of print. PMID: 32555388.

Funding: NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS); Caltech Merkin Institute for Translational Research; George Mason University; European ATAC Consortium; G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation; Robert S. Wennett Post-Doctoral Fellowship; Shapiro-Silverberg Fund for the Advancement of Translational Research; Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

.jpg)

Comment