Norwegian Veterinary Institute Reports Avian H5N1 Spillover Into Red Foxes

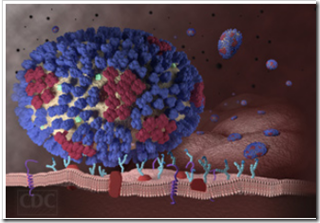

Flu Virus binding to Receptor Cells – Credit CDC

#16,912

Avian influenza viruses - as their name suggests - are primarily adapted to birds, replicating efficiently at the higher body temperatures of avian hosts, and binding preferentially to the alpha 2,3 receptor cells found in the gastrointestinal tract of birds.

Humanized, or mammalian adapted flu viruses, bind preferentially to the α2-6 receptor cells that are abundant in the upper airway (trachea) and lungs. Humans have relatively few α2-3 receptor cells.

Some mammals (like swine, horses, ferrets, etc.) express both types receptor cells in their respiratory tract, making them susceptible to a wider array of flu viruses, and potential `mixing vessels' for influenza viruses (see Viruses: Sialic Acid Receptors: The Key to Solving the Enigma of Zoonotic Virus Spillover).

But to complicate matters, avian influenza viruses can evolve, and adapt to mammalian physiology, particularly after spillover events. And over the past two years, we've seen a growing number of spillover events with avian H5N1 (clade 2.3.4.4b).

Maine: Seal Deaths Linked To Avian H5N1

Quebec: Seal Deaths Linked To Avian H5N1

Two States (Michigan & Minnesota) Report HPAI Infection In Wild Foxes

Ontario: CWHC Reports HPAI H5 Infection With Severe Neurological Signs In Wild Foxes (Vulpes vulpes)

Mutations - such as PB2-627K - can allow the virus to replicate efficiently at the lower temperatures (33°C) commonly found in the respiratory tract of mammals, changes to the virus's RBD (Receptor Binding Domain) can allow it to bind preferentially to the the mammalian α2-6 receptor cell, while other changes (e.g. D701N) can increase virulence.

Less than a week ago, in PrePrint: HPAI H5N1 Infections in Wild Red Foxes Show Neurotropism and Adaptive Virus Mutations, we saw evidence from the Netherlands that Europe's avian H5N1 virus was adapting to its new-found mammalian hosts by acquiring the PB2-627K mutation.

Yesterday the Norwegian Veterinary Institute and the Norwegian Food Safety Authority both issued statements on Norway's first detection of avian H5N1 in a mammalian species (red foxes). First stop, this brief report from the Norwegian Veterinary Institute:

Highly pathogenic bird flu detected in red foxes

Published 30/07/2022

The Veterinary Institute has detected highly pathogenic avian influenza virus in two red foxes from Stad municipality. This is the first time the virus has been detected in species other than birds in Norway.

.jpg)

The Veterinary Institute has detected highly pathogenic avian influenza virus in two red foxes from Stad municipality. This is the first time the virus has been detected in species other than birds in Norway. Photo: Colourbox

In July 2022, two red fox puppies were observed to be ill in Stad municipality, and these were euthanized for animal welfare reasons. Analyzes of swab samples from the throat at the Veterinary Institute showed that both foxes were positive for the highly pathogenic bird flu virus (H5N1).

A number of wild bird species in Norway, including Svalbard and Jan Mayen, were affected by highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in 2021/2022. The outbreak has resulted in high mortality in wild bird populations in some areas, and scavengers, such as red foxes, are exposed to a high infection pressure by eating large quantities of infected birds.

In 2021-2022, sporadic cases of HPAI were detected in Europe in a number of wild mammals, such as red fox, ferret, otter, badger, lynx, harbor seal and otter.

See also EFSA's overview p.34-35 in the report Avian influenza overview March – June 2022

Clinical symptoms of HPAI in carnivores vary, but neurological symptoms such as walking in circles, crooked head position and poor balance are most frequently reported.

It is therefore important that the population is aware of sick animals in areas with proven HPAI in the wild bird population, and reports this to the Norwegian Food Safety Authority. This call applies especially if the predators have neurological symptoms as described above.

Cat and dog owners should be extra aware

Be aware that there may be dead and sick birds in the terrain. Dog and cat owners should follow and keep their pets away from them.

The Norwegian Food Safety Authority has a slightly longer report, with more emphasis on how the public can avoid exposure. I've posted some excerpts below:

(excerpts)

Few known cases of infection to humans

Bird flu is very rarely transmitted from birds to humans, but as a precautionary principle the Norwegian Food Safety Authority recommends taking some precautions.

- We ask everyone to leave sick and dead birds alone. Do not touch them. Don't take a sick bird home to care for it or feed it, says Jahr.

This applies to the species ducks (ducks, geese and swans), gannets, gulls, waders, birds of prey (especially eagles and buzzards) and scavengers (crows).

The Norwegian Food Safety Authority also wants notification of sick carnivores, especially with neurological symptoms (for example walking in circles, crooked head position and poor balance), in areas where highly pathogenic avian influenza virus has been detected in wild birds.

No cases in pets in Norway

Cats or other pets are unlikely to be infected by this virus. The bird flu that has now been detected primarily poses a risk to birds. Bird flu has not been detected in pets in Norway, and only in very few cases internationally.

- Dog and cat owners should still try to keep their animals away from dead and clearly sick birds. As usual, you should also remember good hand hygiene when

handling dogs and cats and wash your hands before eating, says Jahr.

While the future course of avian H5Nx (clade 2.3.4.4b) is unknowable, this virus has made unmistakable progress in its ability to infect, and seriously sicken, mammalian species over the past couple of years.

Human infections, so far, have been few and very mild. Nevertheless, just over 10 weeks ago the CDC Added Zoonotic Avian A/H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4b To IRAT List.

But non-human mammalian species (foxes, seals, and European polecats) have fared far worse, suffering serious - even fatal - infections, often with neurological manifestations.

While there are some who believe that only H1, H2, and H3 viruses have what it takes to spark a human influenza pandemic (see Are Influenza Pandemic Viruses Members Of An Exclusive Club?), 20 years ago the idea that a coronavirus could spark a severe pandemic would have been considered laughable.

H5N1 isn't a huge threat (except to wild and captive birds) today, but what this virus `learns' from infecting foxes, seals, or ferrets now could someday make it into a much bigger threat to humans.

And with viruses, `someday' could mean decades from now, or perhaps as soon as tomorrow.

https://afludiary.blogspot.com/2022/...e-reports.html

Flu Virus binding to Receptor Cells – Credit CDC

#16,912

Avian influenza viruses - as their name suggests - are primarily adapted to birds, replicating efficiently at the higher body temperatures of avian hosts, and binding preferentially to the alpha 2,3 receptor cells found in the gastrointestinal tract of birds.

Humanized, or mammalian adapted flu viruses, bind preferentially to the α2-6 receptor cells that are abundant in the upper airway (trachea) and lungs. Humans have relatively few α2-3 receptor cells.

Some mammals (like swine, horses, ferrets, etc.) express both types receptor cells in their respiratory tract, making them susceptible to a wider array of flu viruses, and potential `mixing vessels' for influenza viruses (see Viruses: Sialic Acid Receptors: The Key to Solving the Enigma of Zoonotic Virus Spillover).

But to complicate matters, avian influenza viruses can evolve, and adapt to mammalian physiology, particularly after spillover events. And over the past two years, we've seen a growing number of spillover events with avian H5N1 (clade 2.3.4.4b).

Maine: Seal Deaths Linked To Avian H5N1

Quebec: Seal Deaths Linked To Avian H5N1

Two States (Michigan & Minnesota) Report HPAI Infection In Wild Foxes

Ontario: CWHC Reports HPAI H5 Infection With Severe Neurological Signs In Wild Foxes (Vulpes vulpes)

Mutations - such as PB2-627K - can allow the virus to replicate efficiently at the lower temperatures (33°C) commonly found in the respiratory tract of mammals, changes to the virus's RBD (Receptor Binding Domain) can allow it to bind preferentially to the the mammalian α2-6 receptor cell, while other changes (e.g. D701N) can increase virulence.

Less than a week ago, in PrePrint: HPAI H5N1 Infections in Wild Red Foxes Show Neurotropism and Adaptive Virus Mutations, we saw evidence from the Netherlands that Europe's avian H5N1 virus was adapting to its new-found mammalian hosts by acquiring the PB2-627K mutation.

Yesterday the Norwegian Veterinary Institute and the Norwegian Food Safety Authority both issued statements on Norway's first detection of avian H5N1 in a mammalian species (red foxes). First stop, this brief report from the Norwegian Veterinary Institute:

Highly pathogenic bird flu detected in red foxes

Published 30/07/2022

The Veterinary Institute has detected highly pathogenic avian influenza virus in two red foxes from Stad municipality. This is the first time the virus has been detected in species other than birds in Norway.

.jpg)

The Veterinary Institute has detected highly pathogenic avian influenza virus in two red foxes from Stad municipality. This is the first time the virus has been detected in species other than birds in Norway. Photo: Colourbox

In July 2022, two red fox puppies were observed to be ill in Stad municipality, and these were euthanized for animal welfare reasons. Analyzes of swab samples from the throat at the Veterinary Institute showed that both foxes were positive for the highly pathogenic bird flu virus (H5N1).

A number of wild bird species in Norway, including Svalbard and Jan Mayen, were affected by highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in 2021/2022. The outbreak has resulted in high mortality in wild bird populations in some areas, and scavengers, such as red foxes, are exposed to a high infection pressure by eating large quantities of infected birds.

In 2021-2022, sporadic cases of HPAI were detected in Europe in a number of wild mammals, such as red fox, ferret, otter, badger, lynx, harbor seal and otter.

See also EFSA's overview p.34-35 in the report Avian influenza overview March – June 2022

Clinical symptoms of HPAI in carnivores vary, but neurological symptoms such as walking in circles, crooked head position and poor balance are most frequently reported.

It is therefore important that the population is aware of sick animals in areas with proven HPAI in the wild bird population, and reports this to the Norwegian Food Safety Authority. This call applies especially if the predators have neurological symptoms as described above.

Cat and dog owners should be extra aware

Be aware that there may be dead and sick birds in the terrain. Dog and cat owners should follow and keep their pets away from them.

The Norwegian Food Safety Authority has a slightly longer report, with more emphasis on how the public can avoid exposure. I've posted some excerpts below:

30.7.2022 14:16:38 CEST | The Norwegian Food Safety Authority

(excerpts)

Few known cases of infection to humans

Bird flu is very rarely transmitted from birds to humans, but as a precautionary principle the Norwegian Food Safety Authority recommends taking some precautions.

- We ask everyone to leave sick and dead birds alone. Do not touch them. Don't take a sick bird home to care for it or feed it, says Jahr.

- If you find sick or dead birds, we ask you to notify the Norwegian Food Safety Authority, so that we can assess whether we should move out to take samples, says Jahr.

This applies to the species ducks (ducks, geese and swans), gannets, gulls, waders, birds of prey (especially eagles and buzzards) and scavengers (crows).

The Norwegian Food Safety Authority also wants notification of sick carnivores, especially with neurological symptoms (for example walking in circles, crooked head position and poor balance), in areas where highly pathogenic avian influenza virus has been detected in wild birds.

No cases in pets in Norway

Cats or other pets are unlikely to be infected by this virus. The bird flu that has now been detected primarily poses a risk to birds. Bird flu has not been detected in pets in Norway, and only in very few cases internationally.

- Dog and cat owners should still try to keep their animals away from dead and clearly sick birds. As usual, you should also remember good hand hygiene when

handling dogs and cats and wash your hands before eating, says Jahr.

While the future course of avian H5Nx (clade 2.3.4.4b) is unknowable, this virus has made unmistakable progress in its ability to infect, and seriously sicken, mammalian species over the past couple of years.

Human infections, so far, have been few and very mild. Nevertheless, just over 10 weeks ago the CDC Added Zoonotic Avian A/H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4b To IRAT List.

But non-human mammalian species (foxes, seals, and European polecats) have fared far worse, suffering serious - even fatal - infections, often with neurological manifestations.

While there are some who believe that only H1, H2, and H3 viruses have what it takes to spark a human influenza pandemic (see Are Influenza Pandemic Viruses Members Of An Exclusive Club?), 20 years ago the idea that a coronavirus could spark a severe pandemic would have been considered laughable.

H5N1 isn't a huge threat (except to wild and captive birds) today, but what this virus `learns' from infecting foxes, seals, or ferrets now could someday make it into a much bigger threat to humans.

And with viruses, `someday' could mean decades from now, or perhaps as soon as tomorrow.

https://afludiary.blogspot.com/2022/...e-reports.html

Comment