DATE: Wednesday, March 26, 2025

As spring bird migration brings thousands of birds to Washington state, it also increases the risk of avian influenza (bird flu) spreading through the region. Migratory waterfowl like ducks, geese, and swans, can carry the virus without showing symptoms and can introduce it to local wildlife. This migration typically peaks from March to May, when birds traveling along the Pacific Flyway stop to rest and feed in Washington’s wetlands and coastal areas.

In this blog, we’ll explore how migrating waterfowl spreads avian influenza, what exactly it is, where it came from, symptoms to watch for, preventive measures you can take, and what to do if you suspect your animals have the virus.

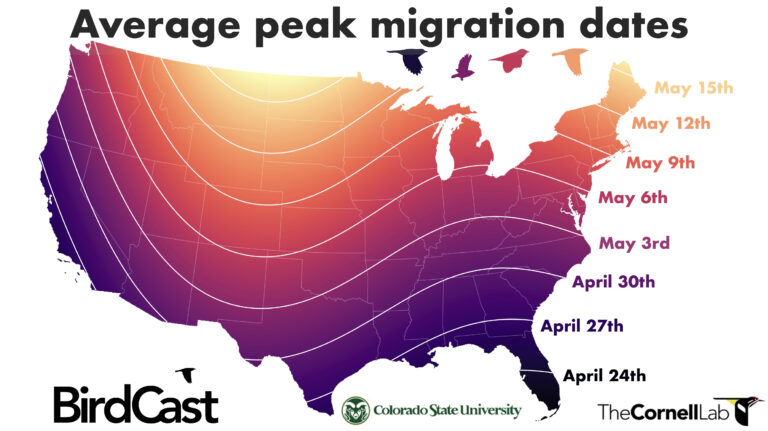

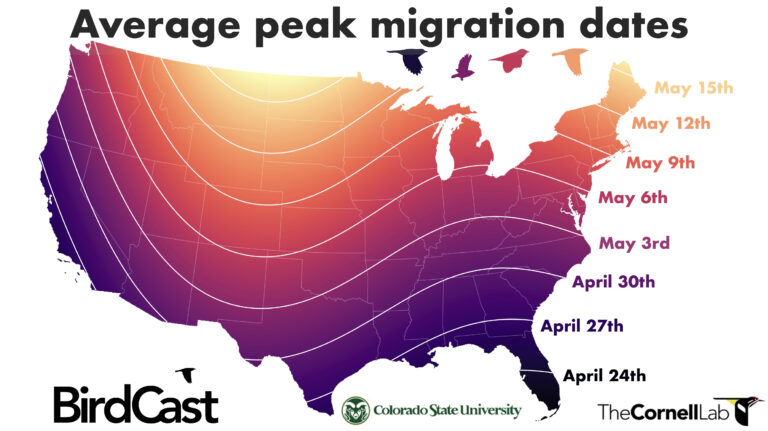

You can track bird migration on the Birdcast website at: https://birdcast.info/. Photo credit: Van Doren, B. M. and Horton, K. G. Year/s of migration forecast map image. BirdCast, migration forecast map; Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Colorado State University and Oxford University. 3/20/2025

The role of bird migration in spreading avian influenza

Waterfowl migration is one of the main ways that avian influenza spreads. Migratory birds traveling along the Pacific Flyway pass through Washington state, bringing with them a mix of avian influenza viruses as their routes overlap, increasing the chance of infected waterfowl sharing viruses.

For example, a wild duck carrying the virus may stop in a wetland or lake and its feces could contaminate the environment. Domestic poultry are then at high risk from the infected waterfowl as they intermingle near water sources. The virus can spread quickly in such environments, devastating entire flocks of poultry.

Photo: Migratory bird flyways in North America., North Dakota Game and Fish Department. https://www.fws.gov/media/migratory-...-north-america. 3/25/2025

What is avian influenza?

Avian influenza is an infectious disease caused by Influenza A viruses (which includes many different strains) that primarily affect wild waterfowl and poultry (such as chickens and ducks). They are particularly adapted to birds and can be deadly, especially to domestic poultry, if it is a highly pathogenic strain.

“Highly pathogenic” avian influenza (HPAI) refers to the ability of a virus to cause severe disease and high mortality rates in poultry.

“Low pathogenic” avian influenza (LPAI) refers to a type that typically causes mild or no clinical signs in infected poultry.

The type of bird flu virus that has been spreading globally is classified as HPAI H5N1.

Certain strains of the virus, such as H5N1 and H7N9, can also infect humans, especially those with close contact to infected poultry or contaminated facilities. Human-to-human transmission is rare but there are concerns that these viruses could mutate to cause a human pandemic. There are many ways that bird flu viruses are monitored to help ensure that any concerning changes are detected right away.

Timeline of key events

The first known outbreak of influenza A is believed to have occurred in Italy in 1878, with the disease later identified in several countries, including the United States, Europe, and Asia, during the early 1900s.

1918 — Spanish flu:

The Spanish flu pandemic, later discovered to be caused by an H1N1 subtype of the influenza A virus, emerges. It infected approximately 500 million people worldwide and causes an estimated 20 — 50 million deaths. This marked one of the deadliest pandemics in human history.

1940s — Development of influenza vaccines:

A bivalent vaccine is developed by Thomas Francis and Jonas Salk at the University of Michigan to protect against both the H1N1 strain of influenza A and the influenza B virus in humans. This is one of the first vaccines against the virus, which later becomes the standard in seasonal human-flu protection.

1960s — Emergence of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI):

Highly pathogenic strains, notably H5N1, begin emerging, causing significant outbreaks in poultry populations. These strains are highly contagious among birds and can cause severe economic losses in the poultry industry.

1996 — H5N1 spreads globally:

H5N1 (HPAI) is identified in waterfowl in Hong Kong. It spread rapidly across the globe, infecting millions of waterfowl and poultry causing significant economic damage to the poultry industry.

1997 — First human cases of H5N1 in Asia:

In 1997, large H5N1 virus outbreaks were detected in poultry in Southeast Asia, and zoonotic (animal to human) transmission led to 18 human infections with six deaths.

2009 — H1N1 pandemic (swine flu):

A new strain of H1N1(low pathogenic), often referred to as "swine flu," emerges and quickly spreads across the globe. H1N1 contains genes from pig, bird, and human influenza viruses so it is not classified as an avian influenza virus. This pandemic caused an estimated 151,700 to 575,400 human deaths worldwide. A vaccine is developed and distributed in response to the global health emergency. H1N1 is now considered a human seasonal influenza A virus.

2013 — H7N9 emergence:

The H7N9 (LPAI in birds but can cause severe illness in humans) strain emerges in China in mostly poultry. It leads to human infections with a high fatality rate. Like H5N1, H7N9 has the potential for a pandemic, though human-to-human transmission remains limited.

2016 — H5N1 and other HPAI strains continue to circulate:

H5N1 continues to circulate globally, alongside other strains such as H5N2, H7N8, H7N2, H5N8, H7N9, and more, which continue to pose a threat to human health and the global poultry industry. Vaccine development for avian influenza strains continues, with increased efforts to create universal vaccines for potential future pandemics.

2022 — First H5N1 case in human in U.S.:

The first reported human case of H5N1 bird flu in the United States occurred in April 2022 in Colorado. The patient recovers.

March 2024 — H5N1 detected in U.S. dairy cattle:

On March 25 the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced that H5N1 had been identified in Texas and Kansas dairy cattle for the first time.

March 2024 — H5N1 detected in domestic cats in U.S.:

The first known cases of H5N1 in domestic cats occurred in March 2024, linked to dairy farms in Michigan, where cats on those farms, including indoor-only cats, became infected.

April 2024 — H5N1 detected in human at U.S. dairy farm:

H5N1 detected in a human case in Texas, involving a worker at a commercial dairy cattle farm where the virus had recently been found in the dairy cattle.

Late 2024 — First cases of domestic cats infected from raw pet food and milk in U.S.:

The first confirmed cases of domestic cats contracting H5N1 avian influenza through contaminated raw pet food occurred in late 2024 and early 2025, with cases and deaths reported in multiple states, including Oregon, Washington, and California.

January 2025 — First human death of H5N1 in U.S.:

On January 6, 2025, the Louisiana Department of Health reported the unfortunate death of a patient after being hospitalized with H5N1 backyard flock and wild birds. This was the first case of severe H5N1 infection requiring critical care support in the U.S. and the second in North America.

Nationwide Detections in Wild and Captive Mammals:

https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-detections/mammals 3/25/2025

Nationwide Detections in Domestic and Commercial Poultry:

https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock...ackyard-flocks 3/25/2025

What are the risks?

Risk to poultry and other farms

Poultry farms are especially susceptible to avian influenza outbreaks because of the close proximity between domestic birds and wild migratory waterfowl, or locations where these birds gather, such as ponds, irrigation canals, lakes, and other waterways where waterfowl land. Poultry often have access to these areas, increasing the risk of exposure to the virus, especially in the winter and spring months when migratory waterfowl are passing through the state.

If the virus is introduced into a farm, it can spread rapidly among domestic poultry, leading to severe illness and death. In most cases, flocks may to be culled to prevent further transmission. The economic and emotional impacts are tremendous, with farmers facing cleanup costs and potential trade restrictions due to the presence of the virus.

Although avian influenza primarily affects waterfowl and poultry, dairy cattle are currently being impacted by the H5N1 virus. However, outbreaks in poultry farms can have ripple effects across the broader agricultural community, especially if trade policies restrict the movement of livestock or animal products, and can also drive up the cost of eggs due to decreased supply from infected farms. Eggs for consumption and eggs for hatching are both in demand, as decimated laying flocks have to be replaced. Chicks are tested for movement into laying houses at about 14-16 weeks, but may not start laying until about 18-20 weeks. All of these things cause an increase in egg prices, and driving people to raise their own flocks.

Risk to household cats

While it’s widely known that bird flu affects wild and domestic birds, there is growing concern about the risk to captive and domestic cats because they are particularly sensitive to the virus.

Cats, especially those that roam outdoors and have access to waterfowl, could get infected with the virus from hunting or consuming infected birds, or from direct contact with infected birds or their environment. Although no direct links have been made with cats contracting the virus directly from waterfowl.

Recently, multiple cats have become infected by consuming contaminated raw milk or raw food. Pet owners should take care to avoid allowing cats to hunt or consume raw food or raw milk that could carry pathogens like avian influenza.

For more information and specific brands and lot number of recalled pet food products in Washington, visit the Washington State Department of Agriculture recalls and health alerts webpage.

Risk to humans

According to the CDC, there have been 70 confirmed human cases and one death associated with H5N1 in the United States as of March 24, 2025. The majority of these cases were associated with exposure to virus-infected dairy cows or poultry.

There have been 14 reported cases of people in Washington becoming infected with avian influenza after exposure to infected poultry that needed to be depopulated.

While the CDC considers the current risk to the general public to be low, people in contact with potentially infected animals or contaminated surfaces or fluids are at higher risk and should take precautions. It is especially important that people in contact with potentially infected animals protect themselves by wearing recommended Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). Public health officials are working closely with local, state, and federal partners to monitor bird flu in Washington. Because influenza viruses constantly change, continuous surveillance and preparedness efforts are critical.

Symptoms of avian influenza

For people: Bird flu symptoms can appear within 1 to 10 days of exposure. People infected with avian influenza have had a range of illness severity, from no symptoms to very serious or life-threatening illness. Anyone who has had contact with or close exposure to animals that are known or suspected to be infected with the virus should be monitored for illness for ten days after the last exposure. Symptoms in people can include:

Symptoms can vary depending on the strain of the virus and the severity of the infection. Symptoms may appear within a few days of infection. Some birds may show no symptoms but still be infected and able to spread the virus. Young birds and birds with weakened immune systems are more susceptible to severe disease. Watch for:

Symptoms may vary depending on the strain of the virus and the individual cat. Some cats may show only mild symptoms, while others may develop severe illness and even death. Watch for:

How to protect farm animals, pets, and yourself

For people:

Where to report

Prevention is your best defense

Avian influenza remains a serious threat to Washington’s ecosystems, agriculture, and even household pets. The risks posed by migratory waterfowl, combined with the potential for transmission to farm animals and household cats, make it crucial for Washington residents to stay informed and take preventive measures. By practicing good biosecurity on farms, limiting pets' outdoor access during migration seasons, and remaining vigilant about sick or dead birds, we can help reduce the spread of bird flu and protect both wildlife and domestic animals.

While the risk to the general public currently remains low, the interconnectedness of wildlife, agriculture, and pets highlights the importance of remaining vigilant and working together to safeguard public health and animal welfare across the state.

Resources:

Federal government webpages:

Washington State government webpages:

Washington State Department of Agriculture blogs:

As spring bird migration brings thousands of birds to Washington state, it also increases the risk of avian influenza (bird flu) spreading through the region. Migratory waterfowl like ducks, geese, and swans, can carry the virus without showing symptoms and can introduce it to local wildlife. This migration typically peaks from March to May, when birds traveling along the Pacific Flyway stop to rest and feed in Washington’s wetlands and coastal areas.

In this blog, we’ll explore how migrating waterfowl spreads avian influenza, what exactly it is, where it came from, symptoms to watch for, preventive measures you can take, and what to do if you suspect your animals have the virus.

You can track bird migration on the Birdcast website at: https://birdcast.info/. Photo credit: Van Doren, B. M. and Horton, K. G. Year/s of migration forecast map image. BirdCast, migration forecast map; Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Colorado State University and Oxford University. 3/20/2025

The role of bird migration in spreading avian influenza

Waterfowl migration is one of the main ways that avian influenza spreads. Migratory birds traveling along the Pacific Flyway pass through Washington state, bringing with them a mix of avian influenza viruses as their routes overlap, increasing the chance of infected waterfowl sharing viruses.

For example, a wild duck carrying the virus may stop in a wetland or lake and its feces could contaminate the environment. Domestic poultry are then at high risk from the infected waterfowl as they intermingle near water sources. The virus can spread quickly in such environments, devastating entire flocks of poultry.

Photo: Migratory bird flyways in North America., North Dakota Game and Fish Department. https://www.fws.gov/media/migratory-...-north-america. 3/25/2025

What is avian influenza?

Avian influenza is an infectious disease caused by Influenza A viruses (which includes many different strains) that primarily affect wild waterfowl and poultry (such as chickens and ducks). They are particularly adapted to birds and can be deadly, especially to domestic poultry, if it is a highly pathogenic strain.

“Highly pathogenic” avian influenza (HPAI) refers to the ability of a virus to cause severe disease and high mortality rates in poultry.

“Low pathogenic” avian influenza (LPAI) refers to a type that typically causes mild or no clinical signs in infected poultry.

The type of bird flu virus that has been spreading globally is classified as HPAI H5N1.

Certain strains of the virus, such as H5N1 and H7N9, can also infect humans, especially those with close contact to infected poultry or contaminated facilities. Human-to-human transmission is rare but there are concerns that these viruses could mutate to cause a human pandemic. There are many ways that bird flu viruses are monitored to help ensure that any concerning changes are detected right away.

Timeline of key events

The first known outbreak of influenza A is believed to have occurred in Italy in 1878, with the disease later identified in several countries, including the United States, Europe, and Asia, during the early 1900s.

1918 — Spanish flu:

The Spanish flu pandemic, later discovered to be caused by an H1N1 subtype of the influenza A virus, emerges. It infected approximately 500 million people worldwide and causes an estimated 20 — 50 million deaths. This marked one of the deadliest pandemics in human history.

1940s — Development of influenza vaccines:

A bivalent vaccine is developed by Thomas Francis and Jonas Salk at the University of Michigan to protect against both the H1N1 strain of influenza A and the influenza B virus in humans. This is one of the first vaccines against the virus, which later becomes the standard in seasonal human-flu protection.

1960s — Emergence of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI):

Highly pathogenic strains, notably H5N1, begin emerging, causing significant outbreaks in poultry populations. These strains are highly contagious among birds and can cause severe economic losses in the poultry industry.

1996 — H5N1 spreads globally:

H5N1 (HPAI) is identified in waterfowl in Hong Kong. It spread rapidly across the globe, infecting millions of waterfowl and poultry causing significant economic damage to the poultry industry.

1997 — First human cases of H5N1 in Asia:

In 1997, large H5N1 virus outbreaks were detected in poultry in Southeast Asia, and zoonotic (animal to human) transmission led to 18 human infections with six deaths.

2009 — H1N1 pandemic (swine flu):

A new strain of H1N1(low pathogenic), often referred to as "swine flu," emerges and quickly spreads across the globe. H1N1 contains genes from pig, bird, and human influenza viruses so it is not classified as an avian influenza virus. This pandemic caused an estimated 151,700 to 575,400 human deaths worldwide. A vaccine is developed and distributed in response to the global health emergency. H1N1 is now considered a human seasonal influenza A virus.

2013 — H7N9 emergence:

The H7N9 (LPAI in birds but can cause severe illness in humans) strain emerges in China in mostly poultry. It leads to human infections with a high fatality rate. Like H5N1, H7N9 has the potential for a pandemic, though human-to-human transmission remains limited.

2016 — H5N1 and other HPAI strains continue to circulate:

H5N1 continues to circulate globally, alongside other strains such as H5N2, H7N8, H7N2, H5N8, H7N9, and more, which continue to pose a threat to human health and the global poultry industry. Vaccine development for avian influenza strains continues, with increased efforts to create universal vaccines for potential future pandemics.

2022 — First H5N1 case in human in U.S.:

The first reported human case of H5N1 bird flu in the United States occurred in April 2022 in Colorado. The patient recovers.

March 2024 — H5N1 detected in U.S. dairy cattle:

On March 25 the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced that H5N1 had been identified in Texas and Kansas dairy cattle for the first time.

March 2024 — H5N1 detected in domestic cats in U.S.:

The first known cases of H5N1 in domestic cats occurred in March 2024, linked to dairy farms in Michigan, where cats on those farms, including indoor-only cats, became infected.

April 2024 — H5N1 detected in human at U.S. dairy farm:

H5N1 detected in a human case in Texas, involving a worker at a commercial dairy cattle farm where the virus had recently been found in the dairy cattle.

Late 2024 — First cases of domestic cats infected from raw pet food and milk in U.S.:

The first confirmed cases of domestic cats contracting H5N1 avian influenza through contaminated raw pet food occurred in late 2024 and early 2025, with cases and deaths reported in multiple states, including Oregon, Washington, and California.

January 2025 — First human death of H5N1 in U.S.:

On January 6, 2025, the Louisiana Department of Health reported the unfortunate death of a patient after being hospitalized with H5N1 backyard flock and wild birds. This was the first case of severe H5N1 infection requiring critical care support in the U.S. and the second in North America.

Nationwide Detections in Wild and Captive Mammals:

https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-detections/mammals 3/25/2025

Nationwide Detections in Domestic and Commercial Poultry:

https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock...ackyard-flocks 3/25/2025

What are the risks?

Risk to poultry and other farms

Poultry farms are especially susceptible to avian influenza outbreaks because of the close proximity between domestic birds and wild migratory waterfowl, or locations where these birds gather, such as ponds, irrigation canals, lakes, and other waterways where waterfowl land. Poultry often have access to these areas, increasing the risk of exposure to the virus, especially in the winter and spring months when migratory waterfowl are passing through the state.

If the virus is introduced into a farm, it can spread rapidly among domestic poultry, leading to severe illness and death. In most cases, flocks may to be culled to prevent further transmission. The economic and emotional impacts are tremendous, with farmers facing cleanup costs and potential trade restrictions due to the presence of the virus.

Although avian influenza primarily affects waterfowl and poultry, dairy cattle are currently being impacted by the H5N1 virus. However, outbreaks in poultry farms can have ripple effects across the broader agricultural community, especially if trade policies restrict the movement of livestock or animal products, and can also drive up the cost of eggs due to decreased supply from infected farms. Eggs for consumption and eggs for hatching are both in demand, as decimated laying flocks have to be replaced. Chicks are tested for movement into laying houses at about 14-16 weeks, but may not start laying until about 18-20 weeks. All of these things cause an increase in egg prices, and driving people to raise their own flocks.

Risk to household cats

While it’s widely known that bird flu affects wild and domestic birds, there is growing concern about the risk to captive and domestic cats because they are particularly sensitive to the virus.

Cats, especially those that roam outdoors and have access to waterfowl, could get infected with the virus from hunting or consuming infected birds, or from direct contact with infected birds or their environment. Although no direct links have been made with cats contracting the virus directly from waterfowl.

Recently, multiple cats have become infected by consuming contaminated raw milk or raw food. Pet owners should take care to avoid allowing cats to hunt or consume raw food or raw milk that could carry pathogens like avian influenza.

For more information and specific brands and lot number of recalled pet food products in Washington, visit the Washington State Department of Agriculture recalls and health alerts webpage.

Risk to humans

According to the CDC, there have been 70 confirmed human cases and one death associated with H5N1 in the United States as of March 24, 2025. The majority of these cases were associated with exposure to virus-infected dairy cows or poultry.

There have been 14 reported cases of people in Washington becoming infected with avian influenza after exposure to infected poultry that needed to be depopulated.

While the CDC considers the current risk to the general public to be low, people in contact with potentially infected animals or contaminated surfaces or fluids are at higher risk and should take precautions. It is especially important that people in contact with potentially infected animals protect themselves by wearing recommended Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). Public health officials are working closely with local, state, and federal partners to monitor bird flu in Washington. Because influenza viruses constantly change, continuous surveillance and preparedness efforts are critical.

Symptoms of avian influenza

For people: Bird flu symptoms can appear within 1 to 10 days of exposure. People infected with avian influenza have had a range of illness severity, from no symptoms to very serious or life-threatening illness. Anyone who has had contact with or close exposure to animals that are known or suspected to be infected with the virus should be monitored for illness for ten days after the last exposure. Symptoms in people can include:

- Fever or chills

- Cough

- Sore throat

- Muscle or body aches

- Congestion, runny or stuffy nose

- Sore throat

- Eye redness, tearing, or irritation

- Difficulty breathing, shortness of breath

- Diarrhea, vomiting

Symptoms can vary depending on the strain of the virus and the severity of the infection. Symptoms may appear within a few days of infection. Some birds may show no symptoms but still be infected and able to spread the virus. Young birds and birds with weakened immune systems are more susceptible to severe disease. Watch for:

- Sudden death (in severe cases)

- Swelling of the head, neck, and eyes

- Discoloration of the comb and wattles (becoming dark or purple)

- Respiratory signs, such as coughing, sneezing, and nasal discharge

- Digestive issues, such as diarrhea

- Decreased egg production or abnormal eggs (soft-shelled or no shells)

- Lethargy or weakness

- Changes in the appearance of feathers (ruffled feathers, unusual positioning)

- Edema (fluid buildup) in the legs and face

- Nervous signs like uncoordinated movements, tremors, or paralysis

Symptoms may vary depending on the strain of the virus and the individual cat. Some cats may show only mild symptoms, while others may develop severe illness and even death. Watch for:

- Fever

- Respiratory distress (e.g., coughing, sneezing, nasal discharge, or difficulty breathing)

- Lethargy or weakness

- Loss of appetite

- Conjunctivitis (inflammation of the eye)

- Diarrhea (in some cases)

- Neurological signs such as uncoordinated movements or seizures (in severe cases)

How to protect farm animals, pets, and yourself

For people:

- Avoid contact with sick or dead waterfowl or poultry, especially in areas with known outbreaks.

- Industry workers that must handle birds that might be infected with bird flu, should wear recommended PPE, which includes safety goggles, gloves, boots or disposable boot covers, an N95 mask or well-fitting face mask, fluid resistant coveralls, and disposable head cover or hair cover.

- Backyard flock owners should wear separate, dedicated shoes and clothing when visiting your chicken run or coop.

- Wash hands thoroughly with soap and water after handling birds or cleaning their cages.

- Cook poultry and eggs thoroughly, as heat kills the virus. Avoid consuming raw milk or products made with raw milk.

- Avoid visiting farms or areas where bird flu is known to be present.

- Restrict direct contact between domestic animals and waterfowl by using physical barriers such as netting, tarps, or fencing to keep them away from farm animals.

- Isolate new animals for 30 days before introducing them to your population.

- Create designated outdoor areas that limit access to waterfowl habitats (ponds, canals, etc.).

- Regularly sanitize equipment, feed, and water containers, and ensure that any feed is stored in a way that minimizes contamination from waterfowl.

- Covering these items prevents potentially infected birds from swooping down and contaminating food and water.

- If possible, keep farm animals sheltered in barns, or in covered areas during peak migration seasons when the risk of exposure is higher.

- Monitor the health of your animals for any signs of illness and report any suspicious cases to local authorities to help prevent a potential outbreak.

- If you have a cat that enjoys going outside, it’s a good idea to supervise their time outdoors, especially during the migratory season.

- Keeping your cat indoors as much as possible can reduce their risk of coming into contact with infected or dead waterfowl.

- Clean your cat’s paws and any areas where they might have come into contact with wildlife. If you live near migratory bird habitats, extra caution is advised.

- Prevent your cat from drinking water from any outside source.

- Avoid feeding your cat raw milk or raw food products.

Where to report

- If you have sick birds in your BACKYARD flock, please report them to WSDA’s Sick Bird Hotline at 1-800-606-3056.

- If you see dead WILD birds, do not touch them! Report them using WDFW’s online reporting tool here: https://survey123.arcgis.com/share/1...49e06d5ad8836a

- If your farm animals or pets are showing symptoms, contact your veterinarian immediately.

- If you have questions about your health, contact your local health jurisdiction or your healthcare provider.

Prevention is your best defense

Avian influenza remains a serious threat to Washington’s ecosystems, agriculture, and even household pets. The risks posed by migratory waterfowl, combined with the potential for transmission to farm animals and household cats, make it crucial for Washington residents to stay informed and take preventive measures. By practicing good biosecurity on farms, limiting pets' outdoor access during migration seasons, and remaining vigilant about sick or dead birds, we can help reduce the spread of bird flu and protect both wildlife and domestic animals.

While the risk to the general public currently remains low, the interconnectedness of wildlife, agriculture, and pets highlights the importance of remaining vigilant and working together to safeguard public health and animal welfare across the state.

Resources:

Federal government webpages:

- CDC: Bird flu in humans

- CDC: Current situation

- USDA Aphis: Detections of HPAI

- US Food & Drug Administration: Recalls, market withdrawals, & safety alerts

Washington State government webpages:

- Washington State Department of Agriculture: Avian Influenza

- Washington State Department of Agriculture: Current bird flu detections in commercial and backyard poultry

- Washington State Department of Agriculture: HPAI in cattle – Producer resources

- Washington State Department of Agriculture: HPAI in cats flyer

- Washington State Department of Agriculture food recalls and health alerts

- Washington State Department of Health Avian Influenza

- Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife

Washington State Department of Agriculture blogs:

- Chicks 101: A beginners guide to raising happy, healthy chickens

- Don’t wing it: Staying ahead of bird flu risks

- Turning crisis into compost: WSDA’s David Hecimovich is fighting avian influenza in California