Overview of U.S. Domestic Response to the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)

February 10, 2020 (R46219)

Contents

Background

On December 31, 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) was informed of a cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan City, Hubei Province of China.1 Illnesses have since been linked to a previously unidentified strain of coronavirus, designated 2019 Novel Coronavirus, or 2019-nCoV. As of February 7, 2020, tens of thousands of people have been infected and over 500 have died, mostly in China.2 The disease has spread to several other countries, including the United States.

On January 30, 2020, the Emergency Committee convened by the WHO Director-General declared the 2019-nCoV outbreak to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC).3 The next day, on January 31, 2020, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Alex Azar declared the outbreak to be a Public Health Emergency pursuant to Public Health Service Act (PHSA) Section 319, retroactively dated to January 27, 2020.4

As the scope of the epidemic widens in China, as of early February, U.S health officials continue to state that the immediate health risk from the new virus to the general American public is low.5 With the situation rapidly changing, both WHO and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) post frequent updates.6

This report discusses selected actions taken by the federal government to quell the introduction and spread of 2019-nCoV in the United States. The HHS Secretary has taken several specific actions to address the 2019-nCoV threat. While some of these actions are based in generally applicable authorities of the Secretary, other authorities may be contingent upon the Secretary or another federal official making a determination or declaration, specific to that authority, regarding the existence of a public health emergency or threat. Each of the actions taken by the Secretary, its statutory basis, and any distinct declarations and determinations supporting the action is presented in this report.

Additional CRS products about this outbreak may be found on the "2019 Novel Coronavirus" Hot Topics tab at www.crs.gov/.

2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)

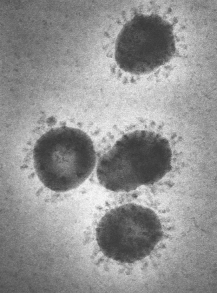

Coronaviruses (see Figure 1) are common respiratory pathogens, usually causing mild illnesses such as the common cold; however, several strains that cause serious illness have emerged in recent years. 2019-nCoV is causing the third serious outbreak of novel coronavirus in modern times, following severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2002 and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2012.7 The global health community is closely monitoring 2019-nCoV because of the severity of symptoms (including death) among those infected and the speed of its spread worldwide. Experts do not know the origin of 2019-nCoV, though genetic analysis and other features suggest an animal source.8

Health officials and researchers are still learning about 2019-nCoV. According to CDC, 2019-nCoV typically causes respiratory infections characterized by a fever, cough, and sometimes breathing difficulty—a suite of symptoms that is common during influenza season.9 Features that have yet to be clarified include routes of transmission (e.g., through the air, from contaminated surfaces); the incubation period (the time between infection and the onset of symptoms); and whether an infected person without symptoms can transmit infection.10 Although it was first reported that 2019-nCoV infections resulted from an animal contact, Chinese officials confirmed person-to-person transmission on January 21, 2020.11 Chinese officials have also reported transmission of the virus from asymptomatic patients.12 However, this finding has yet to be confirmed by U.S. and international health officials and other experts. While WHO and other health experts acknowledge transmission among asymptomatic individuals is possible, scientists agree that asymptomatic transmission is unlikely to be a driver of the outbreak.13

At this time no specific treatment or preventive vaccine exists for 2019-nCoV infections. Care for patients is supportive: maintaining hydration, preventing secondary infections, and providing respiratory support, such as use of a ventilator, if needed.14Domestic Response

In the United States, communicable disease control involves collaboration among federal agencies, state health departments, and international partners. Authority to compel isolation (for sick patients), quarantine (for healthy exposed persons), and disease reporting generally rests in state law.15 The HHS Secretary and, by delegation, CDC have broad authority to assist in the control of communicable diseases through international cooperation, federal-state cooperation, and public health emergency response activities.16 In addition, CDC (by delegation) has explicit authority to detain, examine, and release persons arriving into the United States, and traveling between states, who are suspected of having a communicable disease.17 Other authorities, such as those in the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (INA, P.L. 82-414), allow for other actions relevant to communicable disease control, such as travel restrictions.18

The use of federal and state disease control authorities and other key actions taken in response to the 2019-nCoV outbreak are discussed below. These activities of federal agencies in collaboration with state and local governments include, among others (1) investigation of 2019-nCoV cases and infection control measures in the community, (2) travel restrictions and/or quarantine requirements on certain travelers who have recently visited China, (3) medical countermeasure development, and (4) health system preparedness. Federal agencies involved include several HHS agencies, such as CDC, the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in collaboration with other agencies such as the U.S. Department of State and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Investigation and Control of 2019-nCoV Cases in the Community

To curb the spread of 2019-nCoV cases in the community, state, tribal, and local health departments, with support from CDC, work to identify cases, investigate the possible spread of disease, and take infection control measures.

Case identification begins with testing for 2019-nCoV. CDC urges clinicians to consider a patient's travel and/or contact history and a 14-day incubation period when deciding whether to inform health departments and obtain patient specimens (e.g., mucus, urine) for 2019-nCoV testing. Health care providers are urged to report possible cases to state, tribal, and/or local health departments, which then report to CDC.19

CDC has developed a diagnostic test for the 2019-nCoV virus and initially performed all domestic testing on suspected patients.20 On February 5, 2020, CDC announced that it would begin distributing test kits to state and local laboratories, following an authorization from the FDA (see the "Medical Countermeasures" section for more details).21 CDC has been facilitating the collection and transport of specimens until the diagnostic test is made locally available.22

Once a patient is reported and in the process of having specimens tested, he or she is considered a patient under investigation (PUI) for 2019-nCoV. CDC has developed guidelines for isolation and other precautions for PUIs (including potential PUIs) or those receiving supportive care for 2019-nCoV infection in healthcare settings.23 A key goal of the guidelines is the prevention of disease transmission to health care workers, who may be exposed through high-risk procedures, such as maintaining an ill patient on a ventilator.24

Disease investigation for confirmed cases involves contact tracing—identifying and evaluating individuals who had contact with the patient to determine if transmission has occurred. These investigations are generally conducted by state, tribal, and local health officials, often with support and technical assistance from CDC.25 As of February 3, 2020, CDC has reported two U.S. cases of person-to-person transmission of 2019-nCoV among close household contacts and has indicated that it expects to find additional cases of person-to-person transmission.26

As of February 3, 2020, CDC reported that it had "deployed multidisciplinary teams to Washington, Illinois, California, and Arizona to assist health departments with clinical management, contact tracing, and communications."27 In addition, the Public Health Emergency Declaration by Secretary Azar, pursuant to PHSA Section 319, gives state, local, and tribal health departments more flexibility to reassign personnel to respond to 2019-nCoV if their salaries are funded in whole or in part by PHSA authorized programs.28Travel Restrictions and Quarantine Requirements

Restrictions and Requirements in Effect

CDC and the U.S Department of State have issued advisories to avoid unnecessary travel to China, including a rare Level 4 advisory from the State Department to avoid all travel to China.29 In addition, the Trump Administration has imposed entry restrictions and quarantine requirements in response to the entry of individuals who may pose a risk of introducing the 2019 Novel Coronavirus into the United States.

With respect to entry restrictions, President Trump issued a proclamation on January 31, 2020, that suspends the entry of any foreign national who has been in China within the prior 14 days, subject to some exceptions.30 The exceptions cover lawful permanent residents (LPRs), most immediate relatives of U.S. citizens and LPRs, and some other groups.31 The proclamation directs the Department of State and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to establish procedures for implementing and enforcing the entry restrictions, which by the terms of the proclamation took effect at 5:00 p.m. (EST) on February 2, 2020. For statutory authority, the proclamation relies principally upon Section 212(f) of the INA.32 That statute authorizes the President "to suspend the entry of all aliens or any class of aliens" whose entry he "finds ... would be detrimental to the interests of the United States."33 The Supreme Court has held that Section 212(f) "exudes deference to the President" and gives him mostly unfettered discretion to decide "when to suspend entry," "whose entry to suspend," "for how long," and "on what conditions."34 The presidential proclamation is in effect until terminated by the President.35 The proclamation also directs the HHS Secretary to "recommend that the President continue, modify, or terminate this proclamation."36 Such recommendation is required "no more than 15 days after the date of this order and every 15 days thereafter."37

Quarantine requirements also went into effect on February 2, 2020, according to a DHS announcement.38 All persons, including U.S. nationals, LPRs, and their immediate families who arrive in the United States within 14 days after having been in China are to arrive and be screened at one of 11 designated arrival airports, and such persons may be subject to mandatory quarantine, pursuant to the standing quarantine authorities of the HHS Secretary under PHSA Section 361.39 Persons showing symptoms of illness are to be evaluated by CDC staff to determine if they should be taken to a hospital for medical evaluation and to get care as needed.40 Asymptomatic persons are generally to be held under federal quarantine for up to 14 days if they have traveled from China's Hubei province. However, asymptomatic persons who have traveled from other parts of China may be allowed to self-quarantine for 14 days.41

Personnel from DHS components—namely Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and the Transportation Security Administration (TSA)—are involved in excluding foreign nationals from entry and in assisting CDC personnel with implementation of quarantines for those who are permitted entry under these requirements.42

Of note, in addition to announcing the United States' use of entry restrictions and quarantine authority on January 31, HHS Secretary Azar declared the 2019-nCoV outbreak to be a Public Health Emergency, pursuant to PHSA Section 319.43 This declaration was not statutorily required for the abovementioned entry restrictions and quarantine requirements to go into effect. Each of these authorities is independent of the others. Potential Effects of Travel Restrictions on the Spread of 2019-nCoV

Proposals to restrict the movement of people from affected regions or countries are part of early discussions when novel communicable diseases arise. WHO generally advises against nations imposing travel restrictions on other nations, citing limited evidence of the effectiveness of such measures in controlling outbreaks and the harmful economic effects they have on nations struggling with outbreaks.44 Voluntary movement restrictions are urged instead (see text box below).

In sum, WHO recommends exit screening—screening for symptoms of illness at the point of departure—as preferable to entry screening (i.e., at the point of arrival) as a means to prevent spread of the disease. Other than interventions for individuals who are found to be ill at exit and/or entry screening, WHO does not recommend broader travel restrictions.

The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of communicable diseases is considered poorly understood for several reasons, including (1) limited contemporary examples for study; (2) the inherent variability in the natural progression of global disease outbreaks, even those caused by the same pathogen; (3) variation in actions taken by affected countries and restrictions imposed by other countries; and (4) difficulty in accounting for the effects of nongovernmental actions such as event cancellations and airline flight adjustments. In response to the emergence of 2019-nCoV, China imposed sweeping internal movement restrictions,45 a measure that is likely, in later analyses, to obscure or confound any additional transmission-damping effects that the U.S-imposed travel restrictions may achieve.

Several studies have examined the potential effects of travel restrictions on disease spread, particularly looking at the global spread of influenza and at the SARS outbreak in 2002-2003. Of note, these analyses sometimes indicated delays in the speed of spread of an outbreak. However, the effect of travel restrictions on the ultimate geographic spread of the outbreak—or on the reduction of overall morbidity or mortality—is unclear, and the evidence base is limited. Some studies have found no effect of travel restrictions on overall morbidity and mortality of infectious disease.46 Others have found that very strict travel restrictions may effectively prevent the spread of disease (i.e., complete border closure) or that travel restrictions might be more effective when combined with other infection control measures, such as quarantine and isolation.47 In particular, compulsory movement restrictions may rely on public support in order to be effective, as well as to avoid discrimination and loss of public trust. Many suggest that if public support and trust are essential in any case, enlisting movement restriction through voluntary measures may be just as effective, with less societal disruption.48

In explaining the difference between the United States' response to the 2019-nCoV and the 2009 h1n1 pandemic flu, CDC official Nancy Messonnier stated that in the case of 2019-nCoV, the virus was caught early, before it spread around the world, and that CDC is taking advantage of the window of opportunity to slow its spread into the United States.49

Medical Countermeasures

Potential Products for Use in the 2019-nCoV Response

Medical countermeasures (MCMs) are medical products that may be used to treat, prevent, or diagnose conditions associated with emerging infectious diseases or chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear (CBRN) threats. Examples of MCMs include biologics (e.g., vaccines, monoclonal antibodies), drugs (e.g., antimicrobials, antiretrovirals), and devices (e.g., diagnostic tests and personal protective equipment such as gloves, respirators/masks, and gowns).50 FDA regulates MCMs domestically. Currently, there are no FDA-approved MCMs for 2019-nCoV, although FDA has authorized the use of an unapproved diagnostic test via an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA).51 Federal agencies, pharmaceutical and biotech companies, nongovernmental organizations, and global regulators have been working to expedite the development and availability of MCMs for 2019-nCoV. Examples of such efforts include the following:

On February 5, 2020, BARDA announced an Easy Broad Agency Announcement (EZ-BAA) to solicit applications for development funding of 2019-nCoV molecular diagnostics. The submissions must have a viable plan to meet requirements for the FDA to consider EUA within 12 weeks of an award.55

Scientists in China are testing drugs currently approved for treatment of HIV, influenza (flu), or malaria for potential effectiveness against 2019-nCoV.58 For example, in China, AbbVie's HIV drug Kaletra has been recommended as treatment for patients who have tested positive for 2019-nCoV, while the drug undergoes clinical testing. Johnson & Johnson has reportedly provided its HIV drug Prezcobix to China to test as a potential treatment as well.59 Scientists are also testing many experimental treatments in the research pipeline.60 For example, Gilead is working with health authorities in China to determine whether its experimental antiviral drug Remdesivir can safely and effectively treat 2019-nCoV infections.61

Clinical testing and the FDA review process typically take several years, so it will take time for MCMs in development to reach the commercial market. However, experimental products may become available in the United States prior to FDA approval pursuant to an EUA. FDA encourages industry and government sponsors (e.g., CDC) to engage with FDA prior to submitting a formal request for an EUA, if possible.

Under most circumstances, drugs, medical devices, and biologics may be introduced into interstate commerce only if they have been approved, cleared, or licensed by FDA. Under certain circumstances, however, FDA may permit a medical product to be provided to patients outside the standard regulatory framework, including through issuance of an EUA. In the absence of an approved MCM for 2019-nCoV, FDA may enable access to investigational MCMs by issuing an EUA, if the HHS Secretary declares that circumstances exist to justify the emergency use of an unapproved product or an unapproved use of an approved medical product.66 The HHS Secretary's declaration must be based on one of four determinations; for example, a determination that there is an actual or significant potential for a public health emergency that affects or has significant potential to affect national security or the health and security of United States citizens living abroad.67 Following the HHS Secretary's declaration, FDA, in consultation with ASPR, NIH, and CDC, may issue an EUA authorizing the emergency use of a specific drug, device, or biologic, provided that certain criteria are met (e.g., that there is no adequate, approved, and available alternative to the product).68

On February 4, 2020, the HHS Secretary determined that there is a public health emergency that has a significant potential to affect national security or the health and security of United States citizens living abroad, and that involves the 2019-nCoV.69 This determination allowed FDA to assess and ultimately allow the emergency use of the CDC-developed diagnostic test for 2019-nCoV. This emergency determination by the HHS Secretary is distinct from the Public Health Emergency declaration made pursuant to PHSA Section 319. Health System Preparedness

There is concern that if 2019-nCoV spreads widely in the community, it will overwhelm existing health care system capacity to care for patients and prevent future infections. Given that it is currently flu season, many health care facilities are already at or near patient capacity. The ASPR is the principal advisor to the HHS Secretary on the public health and medical preparedness and response for public health emergencies.70 While 2019-nCoV has not spread widely enough to warrant broad U.S. health system response activities, ASPR and CDC have indicated the following actions in preparation for the potential spread of 2019-nCoV:

CDC and other federal agencies may have the authority needed to respond to the 2019-nCoV epidemic, but their ability to act may be affected by the availability of appropriations. Annual appropriations and standing transfer authority provide the HHS Secretary with some flexibility.75 Upon a declaration of a Public Health Emergency pursuant to PHSA Section 319—which HHS Secretary Azar made on January 31, 2020—HHS may access a Public Health Emergency Fund,76 but the fund does not have an available balance at this time. Separately, funding has generally not been available under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (the Stafford Act) for the response to infectious disease outbreaks. As a result, Congress and the President provided supplemental appropriations for the response to the recent Ebola and Zika virus outbreaks in FY2015 and FY2016.77

In 2018, Congress established an Infectious Diseases Rapid Response Reserve Fund (IDRRRF) for CDC, providing appropriations of $50 million for FY2019 (P.L. 115-245) and $85 million for FY2020 (P.L. 116-94), available until expended.78 These funds may be made available for an infectious disease emergency if the HHS Secretary either (1) declares a Public Health Emergency pursuant PHSA Section 319, or (2) determines that the infectious disease outbreak has significant potential to occur and, if it occurs, the potential to affect national security or the health and security of U.S. citizens, both domestically and abroad.

Before HHS Secretary Azar declared the 2019-nCoV outbreak to be a Public Health Emergency under PHSA Section 319, he issued a determination on January 25, 2020, allowing the allotment of $105 million from the IDRRRF for the 2019-nCoV response.79 Secretary Azar had previously determined that the U.S. response to the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo allowed the use of up to $30 million from the IDRRRF. If both the Ebola and 2019-nCoV amounts are fully used, all funds currently in the IDRRRF would be exhausted.80 On February 2, 2020, HHS reportedly notified Congress of its intention to use the Secretary's standing authority to transfer up to $136 million for 2019-nCoV response efforts, of which $75 million would be made available to CDC, $52 million for ASPR, and $8 million for the HHS Office of Global Affairs.81

CDC has an additional source of emergency support through the CDC Foundation, a 501(c)(3) public charity established by Congress "to support and carry out activities for the prevention and control of diseases, disorders, injuries, and disabilities, and for promotion of public health."82 The CDC Foundation activated its Emergency Response Fund (ERF) to support 2019-nCoV response on January 27, 2020, as requested by CDC.83 Funds have been donated to the ERF for this response by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, among others. Although the support provided by the foundation for outbreak response has been modest compared with supplemental appropriations, the foundation has greater spending flexibility and can sometimes procure response supplies and services more quickly than CDC through federal procurement processes.84

The trajectory of the 2019-nCoV outbreak is uncertain. If the United States experiences sustained person-to-person transmission of the novel virus in the future, the nation's public health and health care systems could be stretched to respond, and resources mobilized from the IDRRRF, HHS transfer authority, and the CDC Foundation may potentially be insufficient. Some Members of Congress have suggested that the Trump Administration consider a request for supplemental funding.85

Author Contact Information

Sarah A. Lister, Coordinator, Specialist in Public Health and Epidemiology ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed])

Kavya Sekar, Coordinator, Analyst in Health Policy ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed])

Agata Dabrowska, Analyst in Health Policy ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed])

Frank Gottron, Section Research Manager ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed])

Audrey Singer, Specialist in Immigration Policy ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed])

Acknowledgments

Edward C. Liu, Legislative Attorney, and Ben Harrington, Legislative Attorney, contributed to this report. Footnotes

February 10, 2020 (R46219)

Contents

- Background

- 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)

- Domestic Response

- Investigation and Control of 2019-nCoV Cases in the Community

- Travel Restrictions and Quarantine Requirements

- Restrictions and Requirements in Effect

- Potential Effects of Travel Restrictions on the Spread of 2019-nCoV

- Medical Countermeasures

- Potential Products for Use in the 2019-nCoV Response

- FDA Emergency Use Authorization (EUA)

- Health System Preparedness

- Response Funding

Background

On December 31, 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) was informed of a cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan City, Hubei Province of China.1 Illnesses have since been linked to a previously unidentified strain of coronavirus, designated 2019 Novel Coronavirus, or 2019-nCoV. As of February 7, 2020, tens of thousands of people have been infected and over 500 have died, mostly in China.2 The disease has spread to several other countries, including the United States.

On January 30, 2020, the Emergency Committee convened by the WHO Director-General declared the 2019-nCoV outbreak to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC).3 The next day, on January 31, 2020, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Alex Azar declared the outbreak to be a Public Health Emergency pursuant to Public Health Service Act (PHSA) Section 319, retroactively dated to January 27, 2020.4

As the scope of the epidemic widens in China, as of early February, U.S health officials continue to state that the immediate health risk from the new virus to the general American public is low.5 With the situation rapidly changing, both WHO and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) post frequent updates.6

This report discusses selected actions taken by the federal government to quell the introduction and spread of 2019-nCoV in the United States. The HHS Secretary has taken several specific actions to address the 2019-nCoV threat. While some of these actions are based in generally applicable authorities of the Secretary, other authorities may be contingent upon the Secretary or another federal official making a determination or declaration, specific to that authority, regarding the existence of a public health emergency or threat. Each of the actions taken by the Secretary, its statutory basis, and any distinct declarations and determinations supporting the action is presented in this report.

Additional CRS products about this outbreak may be found on the "2019 Novel Coronavirus" Hot Topics tab at www.crs.gov/.

| The Response to 2019 Novel Coronavirus: Status as of February 6, 2020 International: Selected World Health Organization (WHO)Declarations https://www.who.int/emergencies/dise...ronavirus-2019

Domestic: Selected Events and United States Government Actions https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/index.html; https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/summary.html; https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/traveladvisories/ea/novel-coronavirus-hubei-province—china.html; and https://www.fda.gov/emergency-prepar...irus-2019-ncov.

|

Coronaviruses (see Figure 1) are common respiratory pathogens, usually causing mild illnesses such as the common cold; however, several strains that cause serious illness have emerged in recent years. 2019-nCoV is causing the third serious outbreak of novel coronavirus in modern times, following severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2002 and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2012.7 The global health community is closely monitoring 2019-nCoV because of the severity of symptoms (including death) among those infected and the speed of its spread worldwide. Experts do not know the origin of 2019-nCoV, though genetic analysis and other features suggest an animal source.8

| Figure 1. Coronaviruses, Electron Micrograph |

|

| Source: CDC Public Health Image Library: https://phil.cdc.gov/Details.aspx?pid=10270. Note: Surface projections on the viral envelope of a poultry coronavirus form the halo or "corona" that gives this virus group its name. |

Health officials and researchers are still learning about 2019-nCoV. According to CDC, 2019-nCoV typically causes respiratory infections characterized by a fever, cough, and sometimes breathing difficulty—a suite of symptoms that is common during influenza season.9 Features that have yet to be clarified include routes of transmission (e.g., through the air, from contaminated surfaces); the incubation period (the time between infection and the onset of symptoms); and whether an infected person without symptoms can transmit infection.10 Although it was first reported that 2019-nCoV infections resulted from an animal contact, Chinese officials confirmed person-to-person transmission on January 21, 2020.11 Chinese officials have also reported transmission of the virus from asymptomatic patients.12 However, this finding has yet to be confirmed by U.S. and international health officials and other experts. While WHO and other health experts acknowledge transmission among asymptomatic individuals is possible, scientists agree that asymptomatic transmission is unlikely to be a driver of the outbreak.13

At this time no specific treatment or preventive vaccine exists for 2019-nCoV infections. Care for patients is supportive: maintaining hydration, preventing secondary infections, and providing respiratory support, such as use of a ventilator, if needed.14Domestic Response

In the United States, communicable disease control involves collaboration among federal agencies, state health departments, and international partners. Authority to compel isolation (for sick patients), quarantine (for healthy exposed persons), and disease reporting generally rests in state law.15 The HHS Secretary and, by delegation, CDC have broad authority to assist in the control of communicable diseases through international cooperation, federal-state cooperation, and public health emergency response activities.16 In addition, CDC (by delegation) has explicit authority to detain, examine, and release persons arriving into the United States, and traveling between states, who are suspected of having a communicable disease.17 Other authorities, such as those in the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (INA, P.L. 82-414), allow for other actions relevant to communicable disease control, such as travel restrictions.18

The use of federal and state disease control authorities and other key actions taken in response to the 2019-nCoV outbreak are discussed below. These activities of federal agencies in collaboration with state and local governments include, among others (1) investigation of 2019-nCoV cases and infection control measures in the community, (2) travel restrictions and/or quarantine requirements on certain travelers who have recently visited China, (3) medical countermeasure development, and (4) health system preparedness. Federal agencies involved include several HHS agencies, such as CDC, the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in collaboration with other agencies such as the U.S. Department of State and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Investigation and Control of 2019-nCoV Cases in the Community

To curb the spread of 2019-nCoV cases in the community, state, tribal, and local health departments, with support from CDC, work to identify cases, investigate the possible spread of disease, and take infection control measures.

Case identification begins with testing for 2019-nCoV. CDC urges clinicians to consider a patient's travel and/or contact history and a 14-day incubation period when deciding whether to inform health departments and obtain patient specimens (e.g., mucus, urine) for 2019-nCoV testing. Health care providers are urged to report possible cases to state, tribal, and/or local health departments, which then report to CDC.19

CDC has developed a diagnostic test for the 2019-nCoV virus and initially performed all domestic testing on suspected patients.20 On February 5, 2020, CDC announced that it would begin distributing test kits to state and local laboratories, following an authorization from the FDA (see the "Medical Countermeasures" section for more details).21 CDC has been facilitating the collection and transport of specimens until the diagnostic test is made locally available.22

Once a patient is reported and in the process of having specimens tested, he or she is considered a patient under investigation (PUI) for 2019-nCoV. CDC has developed guidelines for isolation and other precautions for PUIs (including potential PUIs) or those receiving supportive care for 2019-nCoV infection in healthcare settings.23 A key goal of the guidelines is the prevention of disease transmission to health care workers, who may be exposed through high-risk procedures, such as maintaining an ill patient on a ventilator.24

Disease investigation for confirmed cases involves contact tracing—identifying and evaluating individuals who had contact with the patient to determine if transmission has occurred. These investigations are generally conducted by state, tribal, and local health officials, often with support and technical assistance from CDC.25 As of February 3, 2020, CDC has reported two U.S. cases of person-to-person transmission of 2019-nCoV among close household contacts and has indicated that it expects to find additional cases of person-to-person transmission.26

As of February 3, 2020, CDC reported that it had "deployed multidisciplinary teams to Washington, Illinois, California, and Arizona to assist health departments with clinical management, contact tracing, and communications."27 In addition, the Public Health Emergency Declaration by Secretary Azar, pursuant to PHSA Section 319, gives state, local, and tribal health departments more flexibility to reassign personnel to respond to 2019-nCoV if their salaries are funded in whole or in part by PHSA authorized programs.28Travel Restrictions and Quarantine Requirements

Restrictions and Requirements in Effect

CDC and the U.S Department of State have issued advisories to avoid unnecessary travel to China, including a rare Level 4 advisory from the State Department to avoid all travel to China.29 In addition, the Trump Administration has imposed entry restrictions and quarantine requirements in response to the entry of individuals who may pose a risk of introducing the 2019 Novel Coronavirus into the United States.

With respect to entry restrictions, President Trump issued a proclamation on January 31, 2020, that suspends the entry of any foreign national who has been in China within the prior 14 days, subject to some exceptions.30 The exceptions cover lawful permanent residents (LPRs), most immediate relatives of U.S. citizens and LPRs, and some other groups.31 The proclamation directs the Department of State and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to establish procedures for implementing and enforcing the entry restrictions, which by the terms of the proclamation took effect at 5:00 p.m. (EST) on February 2, 2020. For statutory authority, the proclamation relies principally upon Section 212(f) of the INA.32 That statute authorizes the President "to suspend the entry of all aliens or any class of aliens" whose entry he "finds ... would be detrimental to the interests of the United States."33 The Supreme Court has held that Section 212(f) "exudes deference to the President" and gives him mostly unfettered discretion to decide "when to suspend entry," "whose entry to suspend," "for how long," and "on what conditions."34 The presidential proclamation is in effect until terminated by the President.35 The proclamation also directs the HHS Secretary to "recommend that the President continue, modify, or terminate this proclamation."36 Such recommendation is required "no more than 15 days after the date of this order and every 15 days thereafter."37

Quarantine requirements also went into effect on February 2, 2020, according to a DHS announcement.38 All persons, including U.S. nationals, LPRs, and their immediate families who arrive in the United States within 14 days after having been in China are to arrive and be screened at one of 11 designated arrival airports, and such persons may be subject to mandatory quarantine, pursuant to the standing quarantine authorities of the HHS Secretary under PHSA Section 361.39 Persons showing symptoms of illness are to be evaluated by CDC staff to determine if they should be taken to a hospital for medical evaluation and to get care as needed.40 Asymptomatic persons are generally to be held under federal quarantine for up to 14 days if they have traveled from China's Hubei province. However, asymptomatic persons who have traveled from other parts of China may be allowed to self-quarantine for 14 days.41

Personnel from DHS components—namely Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and the Transportation Security Administration (TSA)—are involved in excluding foreign nationals from entry and in assisting CDC personnel with implementation of quarantines for those who are permitted entry under these requirements.42

Of note, in addition to announcing the United States' use of entry restrictions and quarantine authority on January 31, HHS Secretary Azar declared the 2019-nCoV outbreak to be a Public Health Emergency, pursuant to PHSA Section 319.43 This declaration was not statutorily required for the abovementioned entry restrictions and quarantine requirements to go into effect. Each of these authorities is independent of the others. Potential Effects of Travel Restrictions on the Spread of 2019-nCoV

Proposals to restrict the movement of people from affected regions or countries are part of early discussions when novel communicable diseases arise. WHO generally advises against nations imposing travel restrictions on other nations, citing limited evidence of the effectiveness of such measures in controlling outbreaks and the harmful economic effects they have on nations struggling with outbreaks.44 Voluntary movement restrictions are urged instead (see text box below).

In sum, WHO recommends exit screening—screening for symptoms of illness at the point of departure—as preferable to entry screening (i.e., at the point of arrival) as a means to prevent spread of the disease. Other than interventions for individuals who are found to be ill at exit and/or entry screening, WHO does not recommend broader travel restrictions.

The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of communicable diseases is considered poorly understood for several reasons, including (1) limited contemporary examples for study; (2) the inherent variability in the natural progression of global disease outbreaks, even those caused by the same pathogen; (3) variation in actions taken by affected countries and restrictions imposed by other countries; and (4) difficulty in accounting for the effects of nongovernmental actions such as event cancellations and airline flight adjustments. In response to the emergence of 2019-nCoV, China imposed sweeping internal movement restrictions,45 a measure that is likely, in later analyses, to obscure or confound any additional transmission-damping effects that the U.S-imposed travel restrictions may achieve.

Several studies have examined the potential effects of travel restrictions on disease spread, particularly looking at the global spread of influenza and at the SARS outbreak in 2002-2003. Of note, these analyses sometimes indicated delays in the speed of spread of an outbreak. However, the effect of travel restrictions on the ultimate geographic spread of the outbreak—or on the reduction of overall morbidity or mortality—is unclear, and the evidence base is limited. Some studies have found no effect of travel restrictions on overall morbidity and mortality of infectious disease.46 Others have found that very strict travel restrictions may effectively prevent the spread of disease (i.e., complete border closure) or that travel restrictions might be more effective when combined with other infection control measures, such as quarantine and isolation.47 In particular, compulsory movement restrictions may rely on public support in order to be effective, as well as to avoid discrimination and loss of public trust. Many suggest that if public support and trust are essential in any case, enlisting movement restriction through voluntary measures may be just as effective, with less societal disruption.48

In explaining the difference between the United States' response to the 2019-nCoV and the 2009 h1n1 pandemic flu, CDC official Nancy Messonnier stated that in the case of 2019-nCoV, the virus was caught early, before it spread around the world, and that CDC is taking advantage of the window of opportunity to slow its spread into the United States.49

| WHO Current Guidance Regarding International Travel During 2019-nCoV "With the information currently available for the novel coronavirus, WHO advises that measures to limit the risk of exportation or importation of the disease should be implemented, without unnecessary restrictions of international traffic…. Advice for exit screening in countries or areas with ongoing transmission of the novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV (currently People's Republic of China): Conduct exit screening at international airports and ports in the affected areas, with the [aim of] early detection of symptomatic travellers for further evaluation and treatment, and thus prevent exportation of the disease, while minimizing interference with international traffic;…. Advice for entry screening in countries/areas without transmission of the novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV that choose to perform entry screening: The evidence from the past outbreaks shows that effectiveness of entry screening [to prevent disease spread] is uncertain…. Temperature screening to detect potential suspect cases at Point of Entry may miss travellers incubating the disease or travellers concealing fever during travel and may require substantial investments. A focused approach targeting direct flights from affected areas could be more effective and less resource demanding….Currently the northern hemisphere (and China) is in the midst of the winter season when Influenza and other respiratory infections are prevalent. When deciding implementation of entry screening, countries need to take into consideration that travellers with signs and symptoms suggestive of respiratory infection may result from respiratory diseases other than 2019-nCoV, and that their follow-up may impose an additional burden on the health system…. WHO advises against the application of any restrictions of international traffic based on the information currently available on this event." Source: WHO, "Updated WHO Advice for International Traffic in Relation to the Outbreak of the Novel Coronavirus 2019-nCoV," January 27, 2020, https://www.who.int/ith/2019-nCoV_ad...al_traffic/en/. |

Potential Products for Use in the 2019-nCoV Response

Medical countermeasures (MCMs) are medical products that may be used to treat, prevent, or diagnose conditions associated with emerging infectious diseases or chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear (CBRN) threats. Examples of MCMs include biologics (e.g., vaccines, monoclonal antibodies), drugs (e.g., antimicrobials, antiretrovirals), and devices (e.g., diagnostic tests and personal protective equipment such as gloves, respirators/masks, and gowns).50 FDA regulates MCMs domestically. Currently, there are no FDA-approved MCMs for 2019-nCoV, although FDA has authorized the use of an unapproved diagnostic test via an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA).51 Federal agencies, pharmaceutical and biotech companies, nongovernmental organizations, and global regulators have been working to expedite the development and availability of MCMs for 2019-nCoV. Examples of such efforts include the following:

- Diagnostics. CDC developed the 2019-nCoV Real-Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel.52 On February 4, 2020, FDA issued an EUA, which permits the distribution of the unapproved diagnostic test to and for use by state and local partners.53 (EUAs are described in more detail below). Several federal agencies are working with industry partners to develop rapid diagnostic point-of-care tests for 2019-nCoV, including NIH, particularly through the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); ASPR, through the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA); and the Department of Defense (DOD).54

On February 5, 2020, BARDA announced an Easy Broad Agency Announcement (EZ-BAA) to solicit applications for development funding of 2019-nCoV molecular diagnostics. The submissions must have a viable plan to meet requirements for the FDA to consider EUA within 12 weeks of an award.55

- Therapeutics. Research and development into several treatment strategies for 2019-nCoV are underway by federal agencies, international partners, and industry. Drawing from research on the SARS and MERS coronaviruses, NIAID is assessing potential treatment strategies such as antiviral drugs and animal models that can be used to test potential MCMs. In addition, NIAID is developing assays and other research tools to study 2019-nCoV.56 On February 4, 2020, BARDA announced that it would expand an existing collaboration with Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. to develop monoclonal antibodies that could be used to treat 2019-nCoV infections.57 This partnership would build upon an existing technology used to develop monoclonal antibody therapeutics to treat Ebola and MERS.

Scientists in China are testing drugs currently approved for treatment of HIV, influenza (flu), or malaria for potential effectiveness against 2019-nCoV.58 For example, in China, AbbVie's HIV drug Kaletra has been recommended as treatment for patients who have tested positive for 2019-nCoV, while the drug undergoes clinical testing. Johnson & Johnson has reportedly provided its HIV drug Prezcobix to China to test as a potential treatment as well.59 Scientists are also testing many experimental treatments in the research pipeline.60 For example, Gilead is working with health authorities in China to determine whether its experimental antiviral drug Remdesivir can safely and effectively treat 2019-nCoV infections.61

- Vaccines. At least eight different 2019-nCoV vaccine development initiatives among federal agencies, industry, research institutions, and philanthropies have been announced.62 Of note, the NIAID Vaccine Research Center (VRC) is collaborating with the drug company Moderna and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) to advance a vaccine candidate. Moderna expects this vaccine to enter phase 1 clinical testing in the spring of 2020.63 CEPI is also supporting vaccine development by the University of Queensland (Australia) and the drug companies GlaxoSmithKline and Inovio.64 Johnson & Johnson stated that it is mobilizing efforts to develop a possible preventive vaccine candidate against 2019-nCoV.65

Clinical testing and the FDA review process typically take several years, so it will take time for MCMs in development to reach the commercial market. However, experimental products may become available in the United States prior to FDA approval pursuant to an EUA. FDA encourages industry and government sponsors (e.g., CDC) to engage with FDA prior to submitting a formal request for an EUA, if possible.

Under most circumstances, drugs, medical devices, and biologics may be introduced into interstate commerce only if they have been approved, cleared, or licensed by FDA. Under certain circumstances, however, FDA may permit a medical product to be provided to patients outside the standard regulatory framework, including through issuance of an EUA. In the absence of an approved MCM for 2019-nCoV, FDA may enable access to investigational MCMs by issuing an EUA, if the HHS Secretary declares that circumstances exist to justify the emergency use of an unapproved product or an unapproved use of an approved medical product.66 The HHS Secretary's declaration must be based on one of four determinations; for example, a determination that there is an actual or significant potential for a public health emergency that affects or has significant potential to affect national security or the health and security of United States citizens living abroad.67 Following the HHS Secretary's declaration, FDA, in consultation with ASPR, NIH, and CDC, may issue an EUA authorizing the emergency use of a specific drug, device, or biologic, provided that certain criteria are met (e.g., that there is no adequate, approved, and available alternative to the product).68

On February 4, 2020, the HHS Secretary determined that there is a public health emergency that has a significant potential to affect national security or the health and security of United States citizens living abroad, and that involves the 2019-nCoV.69 This determination allowed FDA to assess and ultimately allow the emergency use of the CDC-developed diagnostic test for 2019-nCoV. This emergency determination by the HHS Secretary is distinct from the Public Health Emergency declaration made pursuant to PHSA Section 319. Health System Preparedness

There is concern that if 2019-nCoV spreads widely in the community, it will overwhelm existing health care system capacity to care for patients and prevent future infections. Given that it is currently flu season, many health care facilities are already at or near patient capacity. The ASPR is the principal advisor to the HHS Secretary on the public health and medical preparedness and response for public health emergencies.70 While 2019-nCoV has not spread widely enough to warrant broad U.S. health system response activities, ASPR and CDC have indicated the following actions in preparation for the potential spread of 2019-nCoV:

- Capacity assessment and monitoring. ASPR and CDC are projecting the potential long-term impact of 2019-nCoV and assessing the capacity of the health care system to respond to a larger outbreak. A sustained response could engage the Regional Treatment Network for Ebola and Other Special Pathogens, a tiered health system response network developed with funding provided by Congress for response to the Ebola outbreak in 2015.71

- Supply chain management. Both ASPR and CDC have indicated that they are working with health care and industry partners to ensure an adequate supply of medical products needed to contain the outbreak, such as personal protective equipment (PPE; e.g., surgical masks). A chief concern in supply chain management is that many medical products or drugs are manufactured, at least in part, in China, the epicenter of the current outbreak.72

- Strategic National Stockpile (SNS).The SNS, managed by ASPR, provides select medicines and medical supplies during public health emergencies when local supply chains are disrupted.73 ASPR states it is working to ensure the adequacy of SNS supplies to prepare for the possible spread of 2019-nCoV.

- Mobilization of healthcare surge capacity. ASPR has indicated that it is working to ensure the availability of additional HHS health care support, such as deployment of the National Disaster Medical System (NDMS), in the event that local health care systems require augmentation to respond to the 2019-nCoV outbreak.74

CDC and other federal agencies may have the authority needed to respond to the 2019-nCoV epidemic, but their ability to act may be affected by the availability of appropriations. Annual appropriations and standing transfer authority provide the HHS Secretary with some flexibility.75 Upon a declaration of a Public Health Emergency pursuant to PHSA Section 319—which HHS Secretary Azar made on January 31, 2020—HHS may access a Public Health Emergency Fund,76 but the fund does not have an available balance at this time. Separately, funding has generally not been available under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (the Stafford Act) for the response to infectious disease outbreaks. As a result, Congress and the President provided supplemental appropriations for the response to the recent Ebola and Zika virus outbreaks in FY2015 and FY2016.77

In 2018, Congress established an Infectious Diseases Rapid Response Reserve Fund (IDRRRF) for CDC, providing appropriations of $50 million for FY2019 (P.L. 115-245) and $85 million for FY2020 (P.L. 116-94), available until expended.78 These funds may be made available for an infectious disease emergency if the HHS Secretary either (1) declares a Public Health Emergency pursuant PHSA Section 319, or (2) determines that the infectious disease outbreak has significant potential to occur and, if it occurs, the potential to affect national security or the health and security of U.S. citizens, both domestically and abroad.

Before HHS Secretary Azar declared the 2019-nCoV outbreak to be a Public Health Emergency under PHSA Section 319, he issued a determination on January 25, 2020, allowing the allotment of $105 million from the IDRRRF for the 2019-nCoV response.79 Secretary Azar had previously determined that the U.S. response to the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo allowed the use of up to $30 million from the IDRRRF. If both the Ebola and 2019-nCoV amounts are fully used, all funds currently in the IDRRRF would be exhausted.80 On February 2, 2020, HHS reportedly notified Congress of its intention to use the Secretary's standing authority to transfer up to $136 million for 2019-nCoV response efforts, of which $75 million would be made available to CDC, $52 million for ASPR, and $8 million for the HHS Office of Global Affairs.81

CDC has an additional source of emergency support through the CDC Foundation, a 501(c)(3) public charity established by Congress "to support and carry out activities for the prevention and control of diseases, disorders, injuries, and disabilities, and for promotion of public health."82 The CDC Foundation activated its Emergency Response Fund (ERF) to support 2019-nCoV response on January 27, 2020, as requested by CDC.83 Funds have been donated to the ERF for this response by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, among others. Although the support provided by the foundation for outbreak response has been modest compared with supplemental appropriations, the foundation has greater spending flexibility and can sometimes procure response supplies and services more quickly than CDC through federal procurement processes.84

The trajectory of the 2019-nCoV outbreak is uncertain. If the United States experiences sustained person-to-person transmission of the novel virus in the future, the nation's public health and health care systems could be stretched to respond, and resources mobilized from the IDRRRF, HHS transfer authority, and the CDC Foundation may potentially be insufficient. Some Members of Congress have suggested that the Trump Administration consider a request for supplemental funding.85

Author Contact Information

Sarah A. Lister, Coordinator, Specialist in Public Health and Epidemiology ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed])

Kavya Sekar, Coordinator, Analyst in Health Policy ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed])

Agata Dabrowska, Analyst in Health Policy ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed])

Frank Gottron, Section Research Manager ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed])

Audrey Singer, Specialist in Immigration Policy ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed])

Acknowledgments

Edward C. Liu, Legislative Attorney, and Ben Harrington, Legislative Attorney, contributed to this report. Footnotes

| 1. | World Health Organization (WHO), "Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)," https://www.who.int/westernpacific/e...el-coronavirus. International Health Regulations (2005) require countries to notify the World Health Organization (WHO) of events that may constitute a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). See CRS In Focus IF10022, The Global Health Security Agenda and International Health Regulations. |

| 2. | WHO, "Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Situation Report-17," February 6, 2020, https://www.who.int/docs/default-sou...vrsn=17f0dca_4. |

| 3. | WHO, "Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)," January 30, 2020, https://www.who.int/news-room/detail...h-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov). A PHEIC is defined in the IHR (2005) as "an extraordinary event which is determined, as provided in these Regulations: i) to constitute a public health risk to other States through the international spread of disease; and ii) to potentially require a coordinated international response." This definition implies a situation that is serious, unusual or unexpected; carries implications for public health beyond the affected State's national border; and may require immediate international action. See WHO webpage on PHEIC at https://www.who.int/ihr/procedures/pheic/en/, accessed on January 31, 2020. |

| 4. | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), "Secretary Azar Declares Public Health Emergency for United States for 2019 Novel Coronavirus," press release, January 31, 2020, https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/...ronavirus.html. |

| 5. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), CDC "Media Telebriefing: Update on 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)," February 3, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2...us-update.html. |

| 6. | WHO, "Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Situation Reports," https://www.who.int/emergencies/dise...uation-reports; and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), "2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Situation Summary," https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/summary.html. |

| 7. | CDC, "Human Coronavirus Types," accessed February 4, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/types.html. |

| 8. | Jon Cohen, "Mining Coronavirus Genomes for Clues to the Outbreak's Origins," Science, January 31, 2020, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020...reak-s-origins; and CDC, "2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Situation Summary," updated February 3, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/summary.html. |

| 9. | CDC, "Symptoms—2019 Novel Coronavirus," accessed February 4, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019.../symptoms.html. |

| 10. | CDC, "Transmission—2019 Novel Coronavirus," accessed February 4, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019...nsmission.html. |

| 11. | Matthew Walsh and Han Wei, "Wuhan Virus Update: China Confirms Human-to-Human Transmission," Caixin Global, January 21, 2020, https://www.caixinglobal.com/2020-01...101506555.html. |

| 12. | WHO, "Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Situation Report -12," February 1, 2020, https://www.who.int/docs/default-sou...ep-12-ncov.pdf. |

| 13. | On January 30, details about a cluster of 2019-nCoV cases in Germany thought to have originated from an asymptomatic patient were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine. These findings were later questioned by observers as new information emerged about the index patient and her symptoms at the time of transmission. For further details, see "Transmission of 2019-nCoV Infection from an Asymptomatic Contact in Germany," New England Journal of Medicine, January 30, 2020, and Kai Kupferschmidt, "Study Claiming New Coronavirus can be Transmitted by People Without Symptoms was Flawed," Science, February 3, 2020, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020...onavirus-wrong. |

| 14. | CDC, "2019 Novel Coronavirus: Information for Healthcare Professionals," https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019...hcp/index.html. |

| 15. | CDC, "Legal Authorities for Isolation and Quarantine," https://www.cdc.gov/quarantine/about...isolation.html. |

| 16. | CDC, "Selected Federal Legal Authorities Pertinent to Public Health Emergencies," August 2017, https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/docs/ph-emergencies.pdf. |

| 17. | Interstate Quarantine regulations: 42 C.F.R. Part 70, and Foreign Quarantine regulations: 42 C.F.R. Part 71. |

| 18. | 8 U.S.C. Chapter 12. |

| 19. | Anita Patel, Daniel B. Jernigan, and 2019 n-CoV CDC Response Team, "Initial Public Health Response and Interim Clinical Guidance for the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak—United States, December 31, 2019–February 4, 2020," Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), vol. 69 (February 5, 2020). |

| 20. | CDC, "2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Situation Summary," updated February 3, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/summary.html. |

| 21. | CDC "Media Telebriefing: Update on 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)," February 5, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2...us-update.html. |

| 22. | CDC, "Interim Guidance for Healthcare Professionals," updated February 2, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019...-criteria.html. |

| 23. | CDC, "Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Confirmed 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) or Patients Under Investigation for 2019-nCoV in Healthcare Settings," updated February 3, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019...n-control.html. |

| 24. | Chaolin Huang, Yeming Wang, Xingwang Li, et al., "Clinical features of Patients Infected with 2019 Novel Coronavirus in Wuhan, China," The Lancet, January 24, 2020. |

| 25. | CDC, "Transcript of 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Update," January 27, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2...us-update.html. |

| 26. | CDC, "Transcript for CDC Telebriefing: CDC Update on Novel Coronavirus," February 3, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2...us-update.html. |

| 27. | CDC, "2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Situation Summary," updated February 3, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/summary.html. |

| 28. | HHS, "Secretary Azar Declares Public Health Emergency for United States for 2019 Novel Coronavirus," press release, January 31, 2020, https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/...ronavirus.html. |

| 29. | CDC, "Travel Health Notices: Novel Coronavirus in China," https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices...onavirus-china; and U.S. Department of State, "China Travel Advisory," February 2, 2020, https://travel.state.gov/content/tra...-advisory.html. |

| 30. | The White House, "Proclamation on Suspension of Entry as Immigrants and Nonimmigrants of Persons Who Pose a Risk of Transmitting 2019 Novel Coronavirus," January 31, 2020, https://www.whitehouse.gov/president...l-coronavirus/. |

| 31. | Id. |

| 32. | 8 U.S.C. ? 1182(f). |

| 33. | Id. |

| 34. | Trump v. Hawaii, 138 S. Ct. 2392, 2408 (2018). |

| 35. | Proclamation, supra note 4, ?5. |

| 36. | Id. |

| 37. | Id. |

| 38. | Department of Homeland Security (DHS), "DHS Issues Supplemental Instructions for Inbound Flights with Individuals Who Have Been in China," press release, February 2, 2020, https://www.dhs.gov/news/2020/02/02/...ave-been-china. |

| 39. | 42 U.S.C. ?264. See "Domestic Quarantine and Isolation: Legal Authority and Policies," in CRS Report R43809, Preventing the Introduction and Spread of Ebola in the United States: Frequently Asked Questions; and CDC, "Legal Authorities for Isolation and Quarantine," https://www.cdc.gov/quarantine/about...isolation.html. |

| 40. | CDC, "2019 Novel Coronavirus: Travelers from China Arriving in the United States," https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019...rom-china.html. |

| 41. | DHS, "DHS Issues Supplemental Instructions for Inbound Flights with Individuals Who Have Been in China," press release, February 2, 2020, https://www.dhs.gov/news/2020/02/02/...ave-been-china. |

| 42. | Ibid. |

| 43. | HHS, "Secretary Azar Declares Public Health Emergency for United States for 2019 Novel Coronavirus," press release, January 31, 2020. |

| 44. | See, for example, World Health Organization (WHO), "No Rationale for Travel Restrictions," May 1, 2009, in the context of the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, https://www.who.int/csr/disease/swin...vel_advice/en/. |

| 45. | Michael Levenson, "Scale of China's Wuhan Shutdown Is Believed to Be Without Precedent," The New York Times, January 22, 2020. |

| 46. | Several such studies are discussed in Julia Belluz and Steven Hoffman, "The evidence on travel bans for diseases like coronavirus is clear: They don't work," Vox, January 23, 2020, https://www.vox.com/2020/1/23/210783...rus-travel-ban. |

| 47. | Sukhyun Ryu, Huizhi Gao, Jessica Y. Wong, et al., "Nonpharmaceutical Measures for Pandemic Influenza in Nonhealthcare Settings—International Travel-Related Measures," Emerging Infectious Diseases, vol. 26, no. 5 (May 2020). |

| 48. | Francesca Matthews Pillemer et al., "Predicting Support for Non-pharmaceutical Interventions during Infectious Outbreaks: A Four Region Analysis," Disasters, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 125-145, January, 2015, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4355939/. |

| 49. | CDC, "Transcript for CDC Telebriefing: CDC Update on Novel Coronavirus," February 5, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2...us-update.html. |

| 50. | FDA, "What Are Medical Countermeasures?" accessed February 4, 2020, https://www.fda.gov/emergency-prepar...ountermeasures. |

| 51. | FDA, "Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)," accessed February 4, 2020, https://www.fda.gov/emergency-prepar...irus-2019-ncov. |

| 52. | Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is a very sensitive technique that, in this use, allows the detection of otherwise undetectably low amounts of biological components specific to coronavirus. |

| 53. | FDA, "FDA Takes Significant Step in Coronavirus Response Efforts, Issues Emergency Use Authorization for the First 2019 Novel Coronavirus Diagnostic," February 4, 2020, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/pres...rization-first. |

| 54. | Dr. Anthony Fauci, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), HHS News Conference on Coronavirus, January 28, 2020, https://plus.cq.com/doc/newsmakertranscripts-5822133; and HHS Representative, White House Coronavirus Task Force news conference, January 31, 2020, https://plus.cq.com/doc/newsmakertranscripts-5826415. |

| 55. | HHS, "HHS Seeks Abstract Submissions for 2019-nCoV Diagnostics Development," press release, February 5, 2020, https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/...velopment.html. |

| 56. | Anthony Fauci, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), HHS News Conference on Coronavirus, January 28, 2020, https://plus.cq.com/doc/newsmakertranscripts-5826415; and Hilary Marston, NIAID, "2019 Novel Coronavirus Stakeholder Listening Session Transcript," January 30, 2020, https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/nCo...Transcript.pdf. |

| 57. | HHS, "HHS, Regeneron Collaborate to Develop 2019-nCoV Treatment," February 4, 2020, https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/...treatment.html. |

| 58. | Manli Wang, Ruiyuan Cao, Leike Zhang, et al., "Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro," Cell Research, February 4, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0; and Panu Wongcha-um, "Cocktail of flu, HIV drugs appears to help fight coronavirus: Thai doctors," Reuters, February 2, 2020. |

| 59. | Jared Hopkins, "U.S. Drugmakers Ship Therapies to China, Seeking to Treat Coronavirus," Wall Street Journal, January 27, 2020. |

| 60. | Manli Wang, Ruiyuan Cao, Leike Zhang, et al., "Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro," Cell Research, February 4, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. |

| 61. | Gilead, "Gilead Sciences Statement on the Company's Ongoing Response to the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)," January 31, 2020, https://www.gilead.com/news-and-pres...ew-coronavirus. |

| 62. | Steve Usdin and Karen Tkach Tuzman, "The Race Is on to Develop Therapies and Vaccines for the Coronavirus Outbreak," Biocentury, January 24, 2020, https://www.biocentury.com/article/3...c-technologies. |

| 63. | Moderna, "Moderna Announces Funding Award from CEPI to Accelerate Development of Messenger RNA (mRNA) Vaccine Against Novel Coronavirus," January 23, 2020, https://investors.modernatx.com/news...te-development. |

| 64. | Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, "CEPI and GSK announce collaboration to strengthen the global effort to develop a vaccine for the 2019-nCoV virus," February 3, 2020, https://cepi.net/news_cepi/cepi-and-...19-ncov-virus/. |

| 65. | Johnson & Johnson, Novel Coronavirus, accessed February 4, 2020, https://www.jnj.com/coronavirus. |

| 66. | 21 U.S.C. ?360bbb-3. For additional information, see CRS In Focus IF10745, Emergency Use Authorization and FDA's Related Authorities. |

| 67. | 21 U.S.C. ?360bbb-3(b)(1). A determination by the Secretary of Homeland Security that there is an actual or significant potential for a domestic emergency involving a heightened risk of attack with one or more CBRN agents; a determination by the Secretary of Defense that there is an actual or significant potential for a military emergency involving a heightened risk of attack with either with one or more CBRN agents, or with one or more agents that may cause or are associated with an imminently life-threatening and specific risk to United States military forces; a determination by the HHS Secretary that there is an actual or significant potential for a public health emergency that affects or has significant potential to affect national security or the health and security of United States citizens living abroad, and that involves one or more CBRN agents; or the identification by Secretary Homeland Security of a material threat pursuant to Public Health Service Act ?319F-2. |

| 68. | 21 U.S.C. ?360bbb-3(c). |

| 69. | This determination, made pursuant to Section 564(b)(1)(C) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (21 U.S.C. ?360bbb-3(b)(1)(C)), is noted on page 1 of the letter of authorization from FDA to CDC, advising of the authorization for emergency use of the CDC-developed diagnostic test. This letter is available at "Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) EUA Information" on the FDA webpage "Emergency Use Authorization," https://www.fda.gov/emergency-prepar...-authorization. See also footnote 53. |

| 70. | HHS, "2019 Novel Coronavirus," https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/nCo...s/default.aspx. See also CRS Insight IN11038, U.S. National Health Security: Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress. |

| 71. | HHS, "HPP Funds Regional Treatment Network for Ebola and Other Special Pathogens," https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/pla...pathogens.aspx. |

| 72. | Robert Kadlec, HHS Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), "2019 Novel Coronavirus Stakeholder Listening Session Transcript," January 30, 2020, https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/nCo...Transcript.pdf; and CDC, "CDC Update on Novel Coronavirus," February 5, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2...us-update.html. |

| 73. | HHS, "Strategic National Stockpile," https://www.phe.gov/about/sns/Pages/default.aspx. |

| 74. | The National Disaster Medical System is described in CRS Report R43560, Deployable Federal Assets Supporting Domestic Disaster Response Operations: Summary and Considerations for Congress; and HHS Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), "2019 Novel Coronavirus Stakeholder Listening Session Transcript," January 30, 2020, https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/nCo...Transcript.pdf. |

| 75. | Annual appropriations acts give the HHS Secretary limited authority to transfer funds from one budget account to another within the department. For instance, a provision in the FY2020 HHS appropriations act (P.L. 116-94, Division A, Title II, ?205) generally allows the Secretary to transfer up to 1% of the funds from any given account. However, in general, a recipient account may not be increased by more than 3%. Congressional appropriators must be notified in advance of any transfer. Another FY2020 appropriations provision (P.L. 116-94, Division A, Title V, ?514) addresses the Secretary's authority to reprogram funds from one program, project, or activity in a given budget account to a different program, project, or activity within the same budget account. This provision places certain limits on such actions and clarifies the circumstances in which appropriations committees must be consulted in advance. (See P.L. 115-245.) |

| 76. | See HHS, "Legal Authority with Declaration of Public Health Emergency," https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/sup...fault.aspx#phe. |

| 77. | Rebecca Katz, Aurelia Attal-Juncqua, and Julie E. Fischer, "Funding Public Health Emergency Preparedness in the United States," American Journal of Public Health, vol. 107, suppl. 2, pp. S148-S152, September, 2017, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5594396/. |

| 78. | The IDRRRF authority is codified at 42 U.S.C. ?247d-4a. |

| 79. | CQ Newsmaker Transcripts, "Health and Human Services Secretary Azar Holds News Conference on Coronavirus," January 28, 2020, https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/sup...fault.aspx#phe. |

| 80. | Communication with CDC, January 28, 2020. |

| 81. | Yasmeen Abutaleb and Erica Werner, "HHS Notifies Congress that it May Tap Millions of Additional Dollars for Coronavirus Response," Washington Post, February 3, 2020. Likely the authority described in footnote 75. |

| 82. | Public Health Service Act Section 399G, 42 U.S.C. ?280e–11. See "National Foundation for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention" in CRS Report R46109, Agency-Related Nonprofit Research Foundations and Corporations. |

| 83. | CDC Foundation, "Responding to Coronavirus," https://www.cdcfoundation.org/coronavirus. |

| 84. | See, for example, CDC Foundation, "2018 Ebola Outbreak," https://www.cdcfoundation.org/2018-ebola-outbreak. |

| 85. | Andrew Siddons, "HHS Chases Virus Treatment as Congress Weighs Additional Funds," CQ, February 4, 2020. |

Comment